Data Centers In Space Are Coming: Here's How To Profit

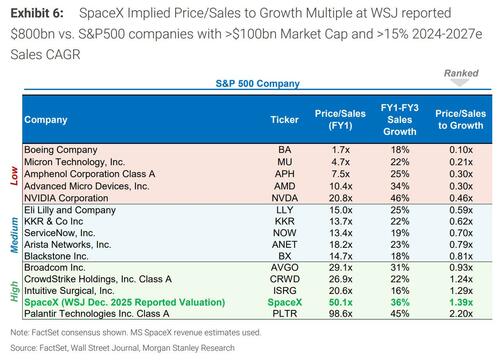

Following SpaceX confirming interest in an IPO next year, reportedly seeking a $1.5 trillion valuation, and Elon Musk expressing strong support for deploying data centers in space, the sellside has started taking a closer look at the concept, with Morgan Stanley and Deutsche Bank publishing almost identical reports days apart.

Cutting to the bottom line: there are clearly technical challenges to making this a viable endeavor but these seem to be engineering constraints as opposed to physics. Moreover, analysts and scientists are encouraged by the fact that Google, OpenAI, and Blue Origin are all seemingly exploring ways to do this. Google’s Project Suncatcher is aiming to launch prototype satellites in 2027 through a partnership with Planet Labs. In addition, OpenAI’s Sam Altman reportedly looked at acquiring a rocket company (Stoke Space) and Eric Schmit actually did acquire one (Relativity Space), in part due to his interest in space-based data centers. Blue Origin also has had a team working on the technology for over a year.

Let's take a closer look at how what until recently would be viewed as wild science fiction can become science fact. For that we excerpt the observations from the Deutsche Bank note (available here to pro subs) and Morgan Stanley research report (available here to pro subs).

Satellite basics

For background, a satellite is typically made up of two main parts: bus and payload. The bus is the main structural framework and support systems of the satellite. It acts as the "vehicle" that enables the satellite to operate in space, maintain its orbit, and survive the harsh environment of vacuum, radiation, and extreme temperatures.

Key components include the physical frame, solar panels, thermal management system, propulsion, and optical terminals. The payload is the specialized equipment or instruments that carry out the satellite's primary mission. For a data center satellite (a DCS), the payload is the GPU or TPU. The bus and payload can be manufactured all in-house (e.g., SpaceX Starlink, Amazon LEO) or can be split up. For reference, last month, upstart Starcloud (formerly known as Lumen Orbit) launched a satellite into orbit with a Nvidia H100 onboard running a LLM, housed in a bus based on Astro Digital’s Corvus-Micro line

Why put these in space?

With AI driving up demand for compute, Earth-based data centers appear to be encountering certain structural bottlenecks, mainly energy, cooling, and latency. DCSs may be able to address these issues.

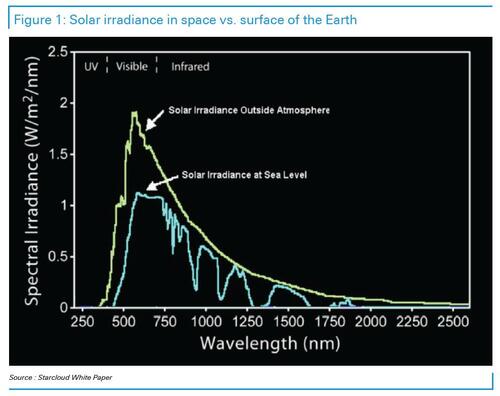

- Energy – at the right orbit such as in dawn-dusk SSO (sun-synchronous orbit), solar panels can harness the sun’s free power 24/7 and importantly, garner 40% higher intensity than on the Earth’s surface due to a lack of an atmosphere filtering/scattering sunlight. As such, operators can generate up to 6-8x more energy in orbit (leveraging continuous availability + greater irradiance) and avoid dealing with expensive/complex power grids terrestrially and also eliminate battery backups.

- Cooling – represents a large burden, accounting for an estimated 40% of energy consumption, having to use large amounts of water/piping. In fact, Nvidia’s Jensen Huang recently commented for a 2-ton GPU rack, 1.95 ton is cooling mass. In space, cooling will require attaching a passive radiator on the dark side of the satellite (i.e., part not facing the sun) which can dump waste into the vacuum of space.

- Latency – optical laser links traveling through vacuum are faster than fiber optic cables on the ground, potentially by >40%. This is due to refractive index of glass and indirect path of travel for cables. In relation, satellites are increasingly generating data in space (e.g., imagery, weather data, climate monitoring). Currently, the data is downlinked to Earth for processing, which is slow and bandwidth-heavy. By having the data centers close to the satellites (“edge compute”), the processing can happen much faster in orbit with only the results/insights being sent back down.

- Scalability – SpaceX today is 90% of mass-to-orbit capacity per Elon Musk. However, as use of re-usable rockets becomes more widespread and competitors like Blue Origin, Rocket Lab, and other emerging launch providers (including China) ramp up cadence, the falling cost per kilogram to orbit and rising total mass-to-orbit capacity is likely to enable larger, more modular deployments of space-based infrastructure.

- Global Edge Connectivity – At scale and when positioned in optimal orbits, space-based datacenters can theoretically improve connectivity for distributed users and edge-compute workloads. By leveraging LEO or mixed orbit constellations, they can theoretically keep compute resources within milliseconds of most population centers, reducing latency compared to long-haul terrestrial paths.

Separately, another intriguing reason is sovereignty or even security. We have observed many local communities protesting data centers being built in their locales and there could be geopolitical concerns in some regions. Terrestrial data centers can also be vulnerable to physical attacks and natural disasters.

What are the challenges?

While the rationale of space data centers makes a lot of sense in theory, there are several key challenges to overcome both in terms of cost and engineering.

- First, rocket launches are still too expensive. A reuseable Falcon 9 commercial launch has a sticker price of ~$70m and let us assume gross margin on that is ~40%, the cost is still likely around $30m, implying a $/kg cost of around $1.5k. According to Google’s Project Suncatcher white paper, launch costs would need to break below $200/kg to be viable which would require a SpaceX Starship to be operational and launching on a regular cadence.

- Second, thermal management will be an issue albeit for different reasons compared to cooling on the ground. While space is cold, it is a vacuum or perfect insulator, meaning heat can only be removed via radiation (slow), as opposed to convection (fast, like a fan blowing air). GPUs are extremely power-dense, generating heat in small, concentrated spots. To properly cool a large AI cluster, a DCS would require massive passive radiator panels. Therefore, some type of breakthrough is required in the radiator design to make the data center truly viable.

- Third, radiation can cause faster degradation of chips. Cosmic rays and high-energy protons constantly bombard the satellite. Interestingly, the Google white paper discovered that based on simulations, TPU logic cores handled radiation quite well but high bandwidth memory (HBM) began showing errors at much lower doses. There are some simple solutions for this such as wrapping the servers in heavy lead or aluminum. However, this would naturally add mass to the satellite.

- Fourth, maintenance appears very impractical in space. Therefore, the satellites may need to be upgraded with higher “space-grade” hardware to ensure longevity, driving up costs. While there have been proposals for orbital transfer vehicles (OTVs) to provide maintenance, the cost of building one capable of carrying advanced maneuvers is too expensive (e.g., need robotic arm essentially to swap out components).

Starlink bold future vision

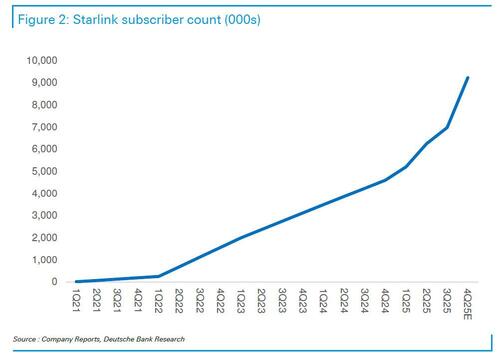

Deutsche Bank forecasts Starlink will break 9 million subscribers exiting 2025E, representing a doubling YoY, once again demonstrating strong momentum and this excludes any D2D users (via MNOs).

Looking ahead, Musk indicated Starlink will develop a modified version of the V3 satellite for data centers. Recall, V3 is equipped with high-speed laser links capable of up to 1 Tbps downlink/throughput but due to its size, must be launched by Starship (see more details here). These satellites will be linked and have onboard compute to process data then beam back down to Earth. In a response on X earlier this month, Musk alluded to 1 megaton/year of satellites with 100 kW per satellite, yielding 100 GW of AI added per year. Assuming V3 has a mass of 1,200-2,000 kg, this translates into a staggering 500-800k satellites. Needless to say, this seems a bit unbelievable and the bank's assumption is the eventual Starlink V4 or V5 DCS will get substantially bigger and more powerful. For context, V3 is designed to deliver 10x more capacity than V2 mini.

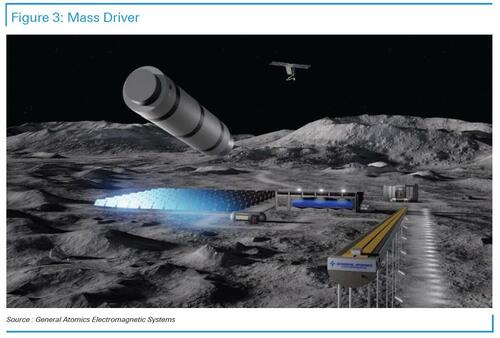

Beyond that, Musk pointed to building satellite factories on the Moon (presumably leveraging Tesla Optimus humanoids) and then using a electromagnetic railgun (also referred to as a “Mass Driver”) to send satellites to lunar escape velocity without the need for rockets. This is because the Moon has just one-sixth the gravity of Earth and no atmosphere (no drag), thereby, requiring less effort to deploy satellites from the Moon. Musk believes this will ultimately allow for scaling up to >100 TW of AI, enabling progress toward becoming a Kardashev II civilization. A Type II Civilization (often called a "Stellar Civilization") is a society capable of harnessing the total energy output of its parent star, allowing it to terraform planets and conduct interstellar travel (which is somewhat optimistic for a plant which can't even balance its budget deficits).

Market implications

From a TAM perspective, Deutsche thinks DCSs represent an entirely incremental opportunity for both launch and satellite manufacturing companies. The

hyperscalers are very well capitalized and can easily fund future deployments if desired which was a concern for some previously proposed LEO mega broadband constellations (e.g., Rivada). Initially, deployments will be small in order to prove out the engineering and economics, beginning in 2027-28 (assuming that China hasn't won the AI race by then). Should these be successful, constellations should reach hundreds and then thousands of satellites in the 2030s. Worth mentioning, there has been pushback advocating that new innovation on the ground can boost energy production and reduce costs sooner – we wonder what happens if some of these big energy projects in the US ramp up slower or get delayed (e.g., nuclear). Who do you believe can move faster: Elon/SpaceX or the energy production apparatus?

In DB's coverage universe, initial screening points to 3 public companies who appear well positioned to benefit should space-based data centers take off. Morgan Stanley has highlighted several more private companies which will likely go public very soon if the space data center concept is proven in the near future.

- Planet Labs (PL) – Planet is already working with Google to develop prototype satellites for a 2027 launch to test out capabilities such as shedding heat from the TPUs and formation flying, ultimately building towards an AI cluster in orbit. Management indicated this was a competitive process, highlighting its ability to produce/validate satellites at high volumes (built, launched, and operated >600 since inception) and at low cost. The bus will be the same as Planet’s next-gen Owl scanning satellite (which itself will have a Nvidia GPU onboard for edge compute) albeit will utilize more solar panels and likely have some other small tweaks.

- Rocket Lab (RKLB) – Rocket Lab can support DCS deployment in multiple ways including helping launch satellites with Neutron but more importantly, it can manufacture satellites at scale using its own bus and produces key components in-house including high efficiency solar cells/ panels and laser optical terminals (through an impending acquisition).

- Intuitive Machines (LUNR) – Through its proposed acquisition of Lanteris, we think IM will gain access to a bus platform which can be used to house GPU/TPU payloads. Lanteris has long standing experience building satellites requiring massive amounts of power and heat dissipation. Its 1300 GEO series can generate +20 kW of power and uses advanced radiators and thermal loops to dissipate heat generated by high-power electronics. Looking ahead, it may need to transfer such capabilities to its 300 LEO series or create a new platform tailored for DCSs.

- Starcloud (Private): Starcloud is a Redmond, Washington–based startup founded in 2024 by Philip Johnston (CEO), Ezra Feilden (CTO), and Adi Oltean (Chief Engineer). The company’s mission is to deploy orbital datacenters that leverage abundant solar power, passive radiative cooling and space-scale infrastructure to serve AI and cloud-compute workloads. Backed by accelerator and seed investors such as Y Combinator, NFX, FUSE VC, and major funds from Andreessen Horowitz and Sequoia Capital, they have raised over $20 million in seed funding according to PitchBook

- Axiom Space (Private): Axiom Space is a Houston-based commercial space infrastructure company founded in 2016 by Michael T. Suffredini and Kam Ghaffarian. The company is developing an “Orbital Data Center” (ODC) product line, with plans to launch its first two free-flying ODC nodes into low Earth orbit by the end of 2025. These nodes aim to provide secure, cloud-enabled data storage and processing for commercial, civil, and national security customers, leveraging partnerships with companies such as Kepler Communications and Spacebilt Inc. for optical inter-satellite links and inspace server systems. According to PitchBook, the company has raised over $700 million to date from investors including Type One Ventures and Deep Tech Fund Advisors.

- Lonestar Data Holdings (Private): Lonestar Data Holdings is a St. Petersburg, Florida-based company founded around 2018 (incorporated in 2021) and led by CEO Christopher Stott. The firm is developing lunar and space-based data-center infrastructure (e.g., its “Freedom” payload was launched aboard Intuitive Machines’ Athena lunar lander via a Falcon 9 rocket to create the first commercial lunar data center.

For a more technical and scientific analysis of on the economics of Orbital Data Centers, please read "Economics of Orbital vs Terrestrial Data Centers" by Andrew McCalip.

Much more in the full Deutsche Bank note (available here to pro subs) and Morgan Stanley research report (available here to pro subs).