How To Inflate Away Your Debt And Alienate People

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

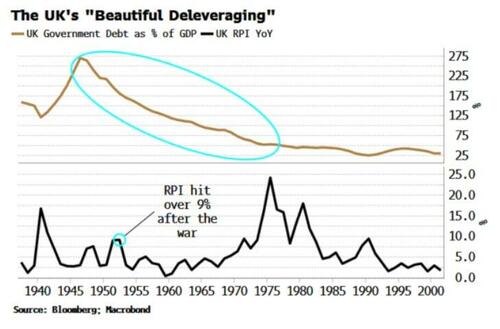

The higher inflation and weaker dollar that US policy points toward is consistent with falling government debt. But rather than the “beautiful deleveraging” achieved by the UK after the Second World War, unpredictable policymaking risks irretrievably damaging trust in the dollar system, provoking capital outflow and adding to the debt burden.

The US is caught in a policy hurricane as it is assaulted by a battery of announcements and directives. Recent backtracking on removing Jerome Powell from the Federal Reserve and easing tariffs on China has pacified markets for now. Amid the uncertainty, however, two market outcomes are looking ever more unavoidable as policy stands: rising inflation and a weaker dollar.

This is sure to be applauded by a fiscally hawkish administration as a way to reduce the US’s near 100% debt to GDP ratio. However, whether it’s part of an implicit plan or not, policy execution is wayward enough that a “good” inflation to reduce debt — as achieved in the UK’s beautiful deleveraging — is one that ends up much more malign, leading to flightier foreign capital, more debt and a loss of faith in the dollar.

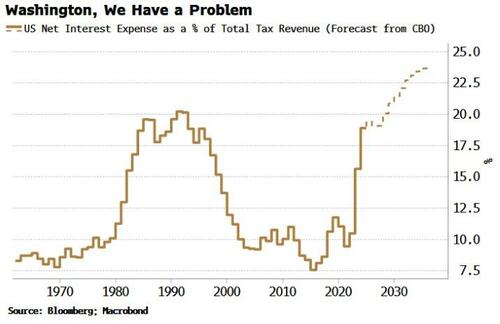

The US undoubtedly has a fiscal problem. Government debt has risen $13 trillion to hit $36 trillion since the beginning of the pandemic. Out of sight but not out of mind, the bill for debt interest is substantial and growing. At 20% of tax revenues, it’s close to as high as it’s ever been and, according to the Congressional Budget Office, set to reach a level where almost $1 in every $4 raised in tax goes to pay the coupons on bonds (almost a third of which are held overseas).

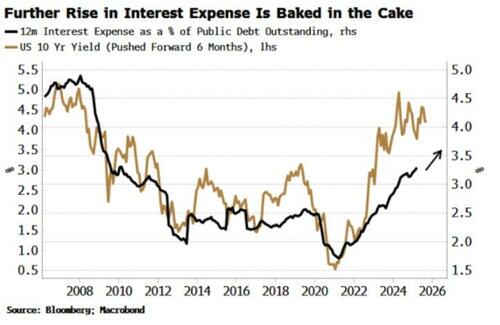

The Treasury market is alive to the burgeoning risks, which is why yields have been rising despite an increasingly negative growth outlook. This inflames the interest bill even more and if sustained threatens to render the CBO’s forecast a significant underestimate given its assumption is based on the 10-year yield averaging only 3.6% over the next 10 years.

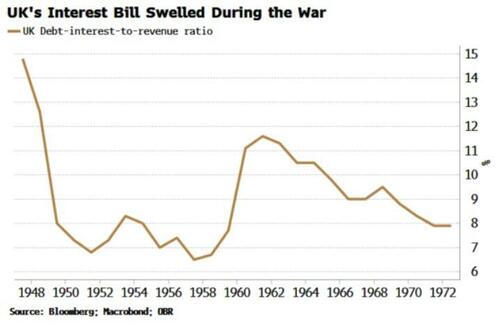

The UK found itself in a similar bind after the Second World War, with its interest bill running at 5% of GDP.

In fact, there are several striking similarities to the US today that merit a closer look.

Note, though, that the chances are slim of America pulling off such a benign reduction in debt as the UK managed. That may not stop a fiscally conservative, at times ideologically driven, US administration from trying. The scarring, though, could end up being deep set: higher yields, capital outflow, lower real returns and a less financially sound dollar.

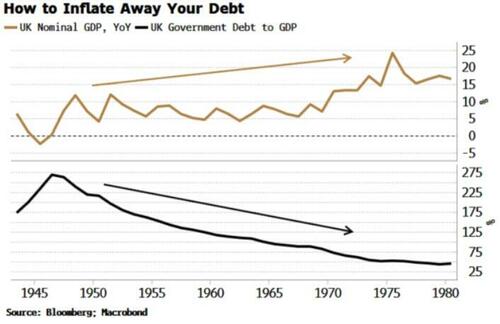

The UK’s debt level after the war reached an eye-watering 270% of GDP. Monetary policy, loosened through the war, was now too loose. Bank credit was rising, and inflation was climbing despite price controls and rationing.

The UK’s interest bill was large but, remarkably, the US today owes more interest in revenue terms than the UK did coming out of an immensely costly six-year conflict (20% versus 15%).

Almost all new debt the UK issued from 1946 to 1976 was to pay interest, a plight the US will surely want to avoid.

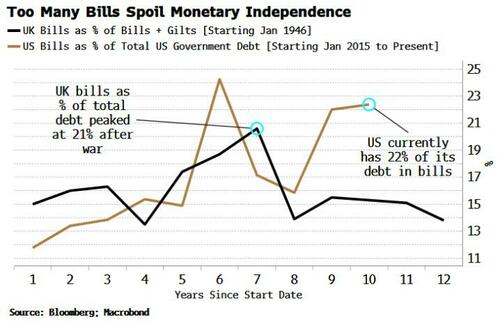

Moreover, a large proportion of UK government debt was in short-term bills, also similar to the US today. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has spoken of the necessity of bringing the proportion of bills down, but since taking office has said he has no immediate plans to curtail their issuance. It would be unsurprising if that was still the aim.

Monetary policy in the UK was therefore entangled with fiscal policy as a tightening of rates would automatically lead to a tightening in government spending, requiring a fiscal or monetary loosening to counteract it.

The UK thus desired to extend the weighted average maturity of its debt to disentwine monetary and fiscal policy. But it could not afford to issue longer-term debt at yields that were climbing as inflation rose.

The costs had to be borne by someone else: no prizes for guessing that meant the public. The UK therefore decided to keep monetary policy looser than it should have been while introducing capital controls, and using “moral suasion” – what we now call financial repression – to coerce banks to swap their bills for longer-term debt issues. That was the UK then; but it’s something that no longer sounds outlandish in the US today.

Over the 30 years after the war, nominal GDP averaged at 8.9% a year. That meant the UK could run a primary budget deficit (ie ex-interest payments) of up to an average of 6.4% of GDP over this period and the debt to GDP ratio would still have fallen (based on Office for Budget Responsibility data).

As it happened the UK ran a primary surplus, and the debt to GDP ratio fell all the way back to around 50% by the mid-1970s.

The motivations for the US to attempt something similar are there: a high and rising debt to GDP ratio, over-reliance on short-term debt and an unsustainable interest bill. However, the UK achieved its deleveraging under the backdrop of a postwar boom and an expansion of global trade – US tariff policy today as it stands is set to result in precisely the opposite.

What rate of nominal GDP would it take for the US to stabilize its debt to GDP? It would need to rise to at least 7% from 5% today. But that assumes the primary budget deficit doesn’t keep rising, and that the average interest rate on debt outstanding also doesn’t increase — both fairly heroic assumptions at this point.

So more inflation might come to be seen as tolerable, perhaps even encouraged. However, that would further undermine the dollar and add to overseas investors’ grounds to take their capital to regions where there is fiscal expansion, leaving higher yields in their wake. Debt to GDP would keep rising if real growth fell by too much.

Path dependency is crucial in politics. Reining in fiscal largesse may be one of the White House’s stated goals, but even if some of the policies are consistent with the outcome — as Liz Truss would attest — it’s all for naught if the path collapses on the way there.