Japan Quietly Changes Bond Market Rules To Avoid Its Own Catastrophic Silicon Valley Bank Moment

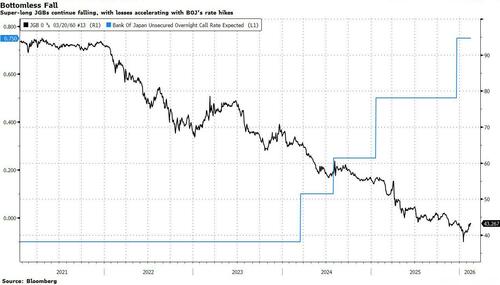

Something remarkable happened a month ago, when Japan's bond market suffered cardiac arrest and when yields on the long-end of the curve shot up to record highs after the BOJ raised rates and politicians proposed tax cuts.

That was when eight long-dated Japanese government bonds issued during the near-zero interest rates era collapsed to well below half of face value, forcing some regional banks to post billions in unrealized losses on securities held to maturity and available for sale.

As Bloomberg wrote on January 21, "Japan’s regional banks are coming under pressure from plunging bond prices reminiscent of Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse in 2023, when devalued Treasury holdings spurred massive unrealized losses and a bank run"

An example of a bond in distressed was the 0.5% coupon 2060 sovereign bond issued five years ago at 99.82 which traded down as low as 38 cents on the yen, with losses accelerating during the BOJ’s rate increases and then really picking up during January's tax cut proposal by that Takaichi admin.

Life Insurers are likely to continue shying away from local bonds due to concern about higher rates, while currency hedge costs constrain purchases of foreign bonds, Steven Lam, Bloomberg Intelligence strategist, wrote.

“The recent JGB turmoil reflects dysfunction in a thin and fragile segment of the ultra-long end,” Taro Kimura, senior Japan economist for Bloomberg Economics, wrote. “These bonds trade in illiquid conditions and are dominated by a narrow base of institutional investors, such as life insurers.”

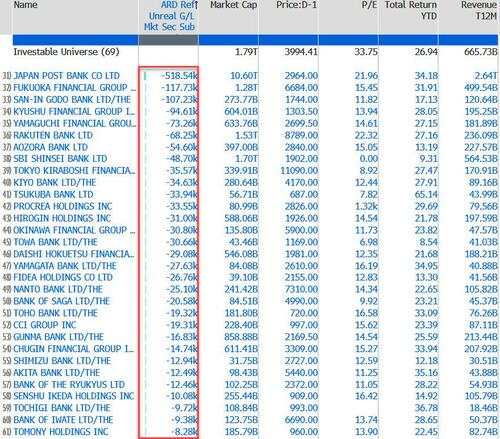

Japanese regional banks, which are smaller and more domestically focused, hold trillions in JGBs bought during the ultra-low rate era, and which have seen about half their value wiped out in recent years. A list of the 30 most impacted banks is shown below (courtesy of Bloomberg), starting with Japan Post bank which is sitting on the largest unrealized losses by far, to the tune of 518 billion yen.

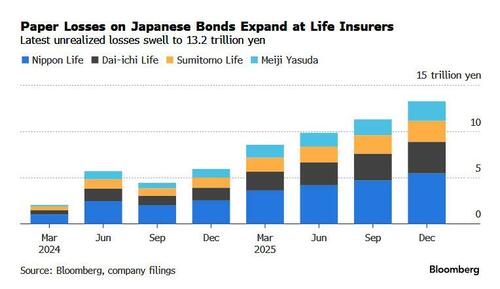

Worse, unrealized losses among Japan's insurers - who are the largest holders of long-dated JGBs (besides the BOJ of course) - are orders of magnitude greater. As the chart below shows, the Big 4 led by Nippon Life are sitting on just under 15 trillion yen in paper losses, or approximately $1 trillion, an absolutely staggering amount for Japan's financial system.

To those suddenly flushed by a sense of Silicon Valley Bank deja vu circa March 2023, you are not alone: this is precisely what is happening in Japan right now, and while the largest mega banks are relatively insulated (after all, if they go, all of Japan goes), their smaller, regional peers are in desperate need of intervention to prevent a bank run which sparks a financial crisis.

And speaking of insurers, in a little noticed report from Jan 22, Bloomberg reported that Japan’s financial regulator "brought forward a regular check on major life insurers’ financial health as it seeks clarity on their unrealized investment losses on rising interest rates."

The Financial Services Agency sent questions to insurers including Nippon Life Insurance Co. over the past week, the people said, asking not to be identified because the matter is private. The survey is seeking details from firms on the amount of unrealized securities losses, responses taken and future investment plans, they added.

The "regular check" by Japan's regulator came as unrealized losses on domestic bonds held by the four firms totaled nearly ¥11.3 trillion ($71 billion) at the end of September, and expanded dramatically by year-end and into January.

But why did the FSA suddenly wake up and start sniffing? That's because under Japanese accounting standards, insurers must report losses on securities when their market value falls below 50% of the acquisition price with no prospect of a recovery.

Well, as noted above, numerous JGBs are now trading well below 50 cents of their purchase price, sparking a flashing red alert that Japan is about to have its own Silicon Valley Bank moment... and with insurers facing even bigger losses, throw in a little AIG crisis to boot.

Or maybe not, if Japan engages in a little creative accounting to shovel its huge bond market mess even deeper under the rug and pretend all is well.

Which is precisely what it has done.

On February 17, the Japanese Institute of Certified Public Accountants announced a proposal to revise the accounting treatment of bonds held by life insurance companies, Nikkei reported. The proposal changes the accounting treatment of "policy reserve-compatible bonds," which are granted to life insurance companies with long-term insurance contracts. In other words, even if bond prices fall due to rising interest rates, they will no longer need to record impairment losses, making it easier to hold government bonds and other bonds for long periods.

This is how Bloomberg explained it: " A Japanese accounting group is seeking to ease rules on how life insurers book paper losses on government bonds, a move that would provide a relief for the major holders of the nation’s debt. Under the proposal, bonds held by life insurers to match long-term policies would be treated as held to maturity if certain conditions are met, and would not be subject to impairment accounting."

The bulk of Japanese insurers’ yen bond holdings are held as so-called policy reserve-matching bonds. Of Dai-ichi Life’s ¥18.7 trillion in yen bond holdings as of Dec. 31, a total of ¥15.7 trillion were in that category.

Translation: Japan just quietly killed mark-to-market accounting for bond holdings, even for those securities that are flagged as Held to Maturity.

Of course, shares of insurers led gains on Wednesday in Tokyo. The Topix Insurance Index closed 2.9% higher, outpacing the benchmark Topix’s 1.2% advance. And why wouldn't it: Japan is literally changing the rules to avoid price - and loss - discovery at companies that are already facing trillions in losses due to their massive JGB holdings.

The accounting change plan provides a tailwind for life insurance stocks, said Ikuo Mitsui, a fund manager at Aizawa Securities Co. If the rule change is implemented, “a factor that depresses short-term earnings would be eliminated, potentially leading to more stable dividends for shareholders,” Mitsui said. Of course, by a "factor depressing short-term earnings", he means losses that are larger than the entity's entire shareholder equity several times over, or said otherwise, if the losses are ever recognized they would lead to immediate insolvency.

As such, the only option is for the bonds to be inflated away prior to maturity, but for that to happen, inflation in Japan would have to be flying and an aging society like Japan's is hardly the best place to experiment with a historic transition from deflation to galloping inflation.

Yet that's precisely what Japan is now trying as its last ditch effort to avoid total financial collapse, one that would be many times greater the US bank crisis from early 2023.

Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Steven Lam said the move would provide a “significant relief” for insurers’ earnings and balance sheets. Insurers have already seen their profits come under pressure from realizing bond losses to pay out on policy surrenders or to capture higher returns after yields surged, he said.

Analysts also see positives for Japan’s bond market. The measure may make it easier for life insurers to buy bonds, according to Naoya Hasegawa, chief bond strategist at Okasan Securities. Likewise, it eases fears that insurers would be forced to sell long-dated JGBs, said Masahiko Loo, a senior fixed-income strategist at State Street Investment Management. “While structural supply demand challenges remain, the guidance reduces accounting-driven selling pressure,” he said.

Here Goldman chimes in, and writes that although the proposed rule change does not change any economics, in reality, lifers sold their JGBs before they breach their threshold for impairment losses. "What's being observed recently is lifers cut losses in JGBs and realize profit in equities to make up the loss. If this rule is introduced, this kind of domino effect may become less."

All of that is true, and the endgame is that instead of selling worthless bonds once they cross a critical threshold of 50 cents on the yen - which while painful would at least serve as a debt brake on the government's spending plans - regional banks and insurers will not only hold on to the huge paper losses, but add even more bond exposure, thus funding even more deficit spending by Japan, which in turn will make the debt crisis that inevitably hits far greater.

But if every crisis since Lehman has taught us one thing, it is that actually fixing the system which is drowning in insurmountable debt is no longer a possibility and the only recourse those in power have is to kick the can for at least a few quarters or years, at which point it will be someone else's problem.