QT Ends Today Amid Repo Surge: What This Means For Overall Liquidity

After a one month self-imposed delay by the Fed which drained tens of billions in liquidity, the Fed's balance sheet runoff (i.e. QT) ends today.

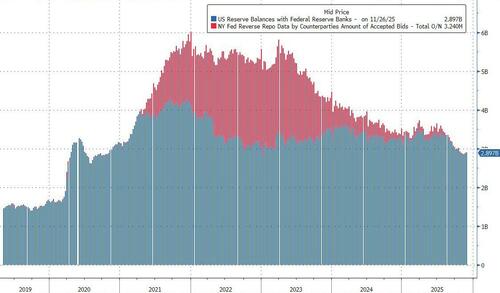

As a reminder, the Fed's quantitative tightening (QT) process began in the middle of 2022, but it wasn't until the second half of 2025 that the cumulative effects of runoff made a lasting dent in the level of reserves. Following the mid-2025 resolution to the debt limit impasse, the rebuild in Treasury's cash balance (the TGA) took the domestic reverse repo (RRP) facility to near zero and reserves held at the Fed sharply lower.

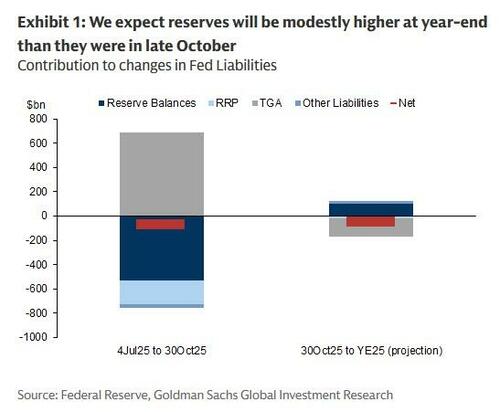

The active process of balance sheet shrinking is set to end today, December 1, and in a note from the bank's rates strategist William Marshall, Goldman Sachs estimates (full note available to pro subs) that reserves should finish the year at around $2.9tn, about $100bn above their late October trough as the TGA dips back towards Treasury's $850bn year-end target following an intra-quarter overshoot.

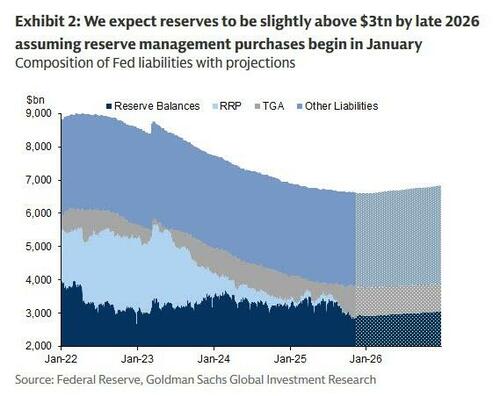

Beyond year-end, a stable Fed balance sheet and modest drift lower in TGA would be consistent with a gradual drift lower in reserves thanks to growth in other Fed liabilities like currency in circulation. However, given recurrent volatility in repo rates and comments from Fed officials suggesting that it likely “will not be long before we reach ample reserves,” there will likely be only a brief period of stability in the overall size of the balance sheet. Echoing our analysis from mid-November, that "Repo Is Locking Up Again As Market Tries To Force Fed's "Reserve Management Purchases", Goldman's baseline is that reserve management purchases will begin in January 2026, with the Fed buying about $20bn Treasury bills per month on an outright basis in addition to the bill purchases to replace maturing MBS (which should average around $20bn per month as well). That shift would gradually boost steady-state reserves to levels modestly above $3tn by the second half of 2026.

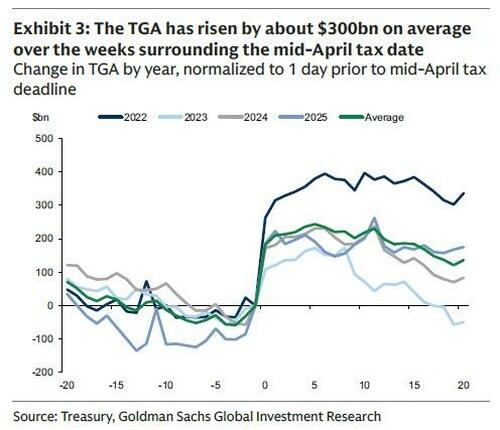

Goldman's $20bn per month projection for reserve management purchases is based on an estimate of what is likely required to accommodate trend growth in currency in circulation and keep reserves roughly stable as a share of bank assets assuming a stable $850bn TGA target. However, seasonal volatility in the TGA - for example, around tax dates- will remain a source of episodic downward pressure on reserves and upward pressure on dollar funding costs. The magnitude of typical TGA swings around the mid-April tax deadline is a factor that we think also favors a relatively quick turnaround from balance sheet runoff to balance sheet expansion.

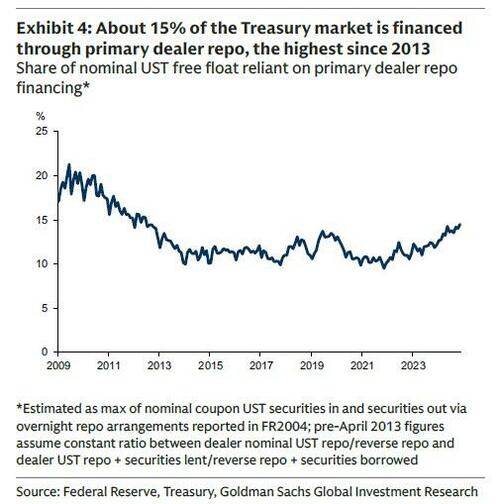

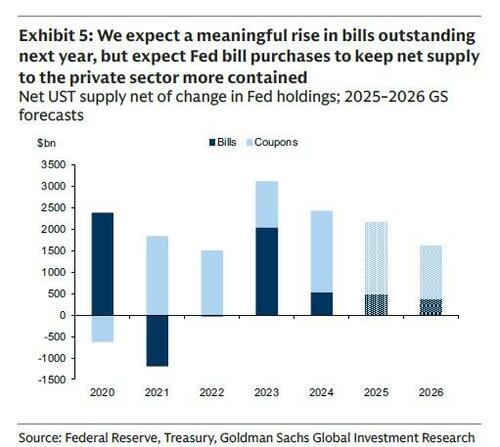

In terms of the sources of demand for financing, Treasury supply remains elevated in aggregate and will likely keep rising as the US budget deficit balloons further. However, the combination of the shift in Fed balance sheet policy and Treasury’s issuance mix implies that net coupon supply net of Fed - i.e. what all non-Fed buyers have to absorb - should be the lowest since 2023 and second lowest since 2020. While the recent uptrend in demand for repo financing relative to the size of the market may continue, a smaller change in free float versus prior years means a smaller increment potentially requiring repo financing assuming a roughly stable mix of buyers.

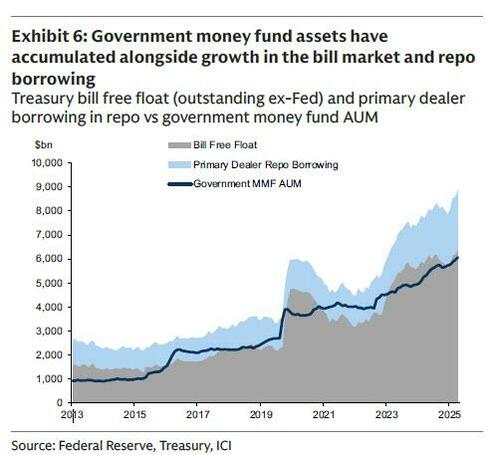

Goldman expects a faster pace of growth in T-bills outstanding, but the bank's baseline for the Fed’s balance sheet policy implies that non-Fed buyers would only need to absorb about $390bn of the projected $870bn in net T-bill issuance, with the Fed buying the remaining $480bn thanks to reserve management purchases and the reinvestment of MBS runoff. That would represent a $100bn deceleration in net T-bill supply ex-Fed versus 2025, and the slowest growth in T-bill free float since 2022.

In terms of the backdrop for front-end absorption, government money fund AUM has been growing at a rate of about $700-750bn per year over the last three years. That has kept the ratio of government money fund assets to the sum of T-bill free float and primary dealer repo borrowing around 70% since the second half of 2023. Goldman's expectation of a steeper Treasury curve and positive equity returns in 2026 are consistent with a deceleration in the pace of money fund AUM accumulation next year. But the slower accumulation of coupon and bill free float suggests that even if money fund AUM growth does moderate, it shouldn’t dramatically shift the balance of front-end supply and demand.

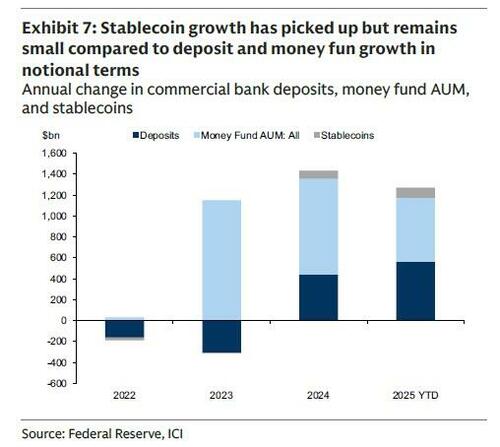

And then there is the "tether wildcard": continued growth in stablecoins could impact the private sector’s mix of short-term or cash-like assets. Passage of the GENIUS Act earlier this year has coincided with continued growth in stablecoins outstanding. However, there isn’t strong empirical evidence that suggests that stablecoin growth is coming at the expense other areas, with the magnitude of that growth still limited compared to growth in deposits and money fund AUM. Meanwhile, the mechanics of financial flows and the overlap between what stablecoins and government money funds can hold suggest that an acceleration in stablecoin growth should be at worst neutral for Treasury funding dynamics (though it could over time bring risks elsewhere in the system as some central banks have warned).

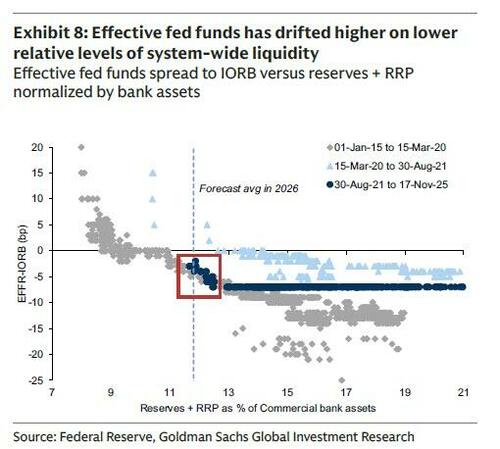

Goldman's baseline for reserves is consistent with a roughly stable effective fed funds rate (EFFR) modestly below interest on reserve balances (IORB). However, as discussed previously, there is risk that oscillations in the TGA - and other exogenous variables - could be a source of more regular volatility at current relative levels of liquidity. Here Goldman's outlook is somewhat complacent, and forecasts that the recent relationship between the EFFR-IORB spread and system-wide liquidity relative to commercial bank assets suggests that an EFFR-IORB spread in the -3 to -1bp range is a reasonable central case.

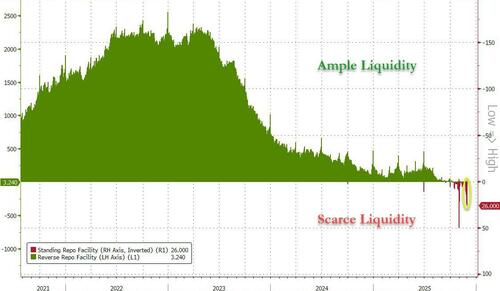

That may prove to be overly optimistic as the ongoing tension in the Standing Repo Facility indicates: while there was an expected spike in month-end usage of the SRF facility, the fact that this has persisted beyond month end on Dec 1, when we observed material $26BN in total facility usage - the second highest since covid - and a signal that overall systemic liquidity remains scarce, indicates that some of the traditional plumbing conduits remain shut.

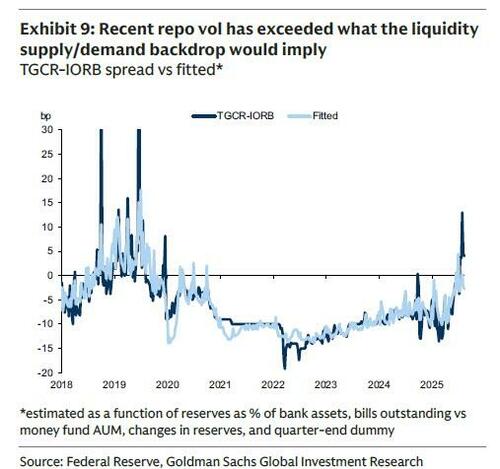

The bank admits as much, writing that "secured funding pressures have risen more sharply than longer term frameworks based on levels and changes in liquidity and front-end supply/demand variables imply." Using longer-term sensitivities suggests a fair value for the triparty general collateral rate (TGCR) that is 2-to-3bp below IORB, and for the secured overnight funding rate (SOFR) that is about flat to or modestly above IORB; and yet realized outcomes for both rates have been about 6bp higher on average over the last couple of weeks.

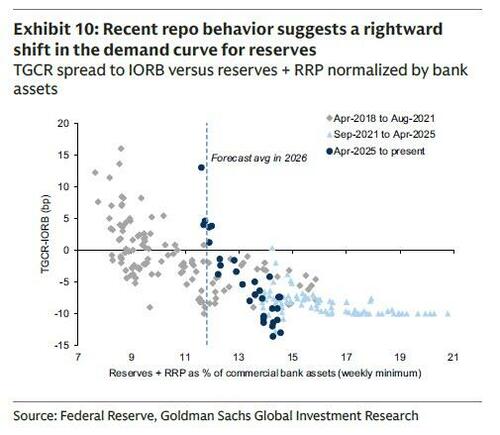

One explanation for the behavior of repo rates since mid-April is a rightward shift in the demand curve for reserves compared to what longer-run estimates would imply. To the extent this is the long-run equilibrium, Goldman concedes that it raises some risk that the Fed may need to take more aggressive steps than the bank forecasts to boost the level of reserves enough to lower the level and volatility in short term funding costs.

The more optimistic take is that the sharp increase in funding volatility reflects frictions in the market’s adjustment to a less abundant liquidity environment given the speed of reserve draining and potential late year bottlenecks. If that’s the case, the observed dynamics may reflect a short-run demand curve for reserves, with a temporary period of higher funding costs acting as the mechanism to encourage a return towards a lower longer-run demand curve (along the lines of the argument laid out by Dallas Fed President Logan).

The SOFR-FF term structure - which implies SOFR between 5 and 6bp above EFFR beyond the first quarter of next year compared to the 10-to-11bp spread realized and implied over the course of Q4 - suggests that the market anticipates a moderation in costs that leave the median SOFR rate close to levels implied by Goldman's longer-run fair value estimates. The bank suspects that reflects some expectation that the Fed will ultimately ensure the system is sufficiently supplied with liquidity to see repo rates anchored closer to IORB, with episodic spikes around settlement and tax dates. There are some risks around the calibration of the size of reserve management purchases that could lead to some bumpiness in funding over the year, keeping the Standing Repo Facility (SRF) a relevant tool. But Goldman's baseline is that latent instability would likely be revealed within several months (i.e. by the April tax date), which leaves expressions such as April/July 2026 SERFF steepeners a potentially useful hedge

Given Goldman's baseline for a relatively stable range for the EFFR, the bank doesn’t see a strong case for a reduction to IORB within the range. Such an adjustment has not featured in comments by Fed officials, and last cycle only occurred when the EFFR was 5bp from the top end of the target range (compared to 12bp below today). That could shift should the Fed start to pivot its focus more explicitly to where secured measures (i.e. TGCR) set within the range, though the possibility of a formal change to the target rate seems some time away still. Significant changes to the SRF - for example a lower rate or move to clearing - seem unlikely for now; it will likely take an episode of funding stress with sustained leakiness in funding costs above the top of the range to prompt changes to parameters that reinforce the facility as a backstop to funding vol (such an outcome would likely only add to the case for reserve management purchases, i.e., the Fed will grow its balance sheet notably faster than what Goldman expects).

* * *

Forecasts aside, here is what we know: going forward, the Fed will keep the System Open Market Account (SOMA) portfolio fixed at the current size of ~$6.1 trillion as of last week. As the Fed indicated in its October FOMC, the central bank will let agency/agency MBS continue to runoff and invest the maturing proceeds in Treasury bills.

Secured funding pressures have risen more sharply than longer term frameworks based on levels and changes in liquidity and front-end supply/demand variables imply (Exhibit 9). Using longer-term sensitivities suggests a fair value for the triparty general collateral rate (TGCR) that is 2-to-3bp below IORB, and for the secured overnight funding rate (SOFR) that is about flat to or modestly above IORB; realized outcomes for both rates have been about 6bp higher on average over the last couple of weeks. Our forecasts for reserves and supply over the next year are constistent with relatively stable fair value estimates.

SOMA has $4.0 trillion Treasurys and $2.05 trillion agency/agency MBS, which as repo guru Scott Skyrm writes (note available to pro subs), "means there's going to be a giant reallocation of collateral across the two markets over the next few years." In other words, two trillion agency/agency MBS are coming into the market and the Fed will absorb $2 trillion of Treasury bill issuance.

In summary: the Fed ends Balance Sheet Runoff today, which will decrease the liquidity drain, although the impact on overall funding conditions remains nebulous. The Fed will absorb $2 trillion in bill issuance, which further decreases the liquidity drain. However, this is done at the expense of the agency/agency MBS market, which will experience a major increase in supply which needs financing and which will put further pressure on the housing market. Meanwhile, the stress in the funding market - exhibited via TGCR rates and SRF usage - will be closely watched by the Fed to determine the pace with which the balance sheet will ultimately resume growth in 2026.

More in the full Goldman and Curvature notes available to pro subs.