'A Ticking Time Bomb': BCA Warns Yen Carry Trade Risk/Reward Is Poor

Authored by Arthur Budaghyan via BCAResearch.com,

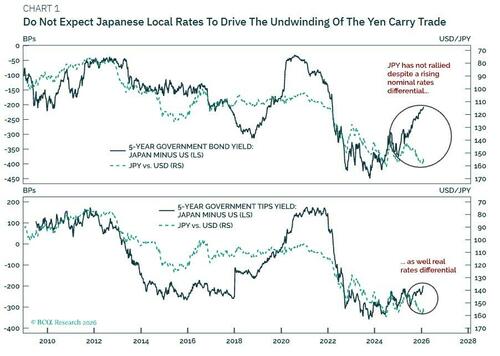

Many investors and commentators expect the yen to appreciate when Japanese interest rates rise in absolute or relative terms. However, the yen has continued to depreciate even as its nominal and real interest rates have risen, and their differentials versus the US have improved (Chart 1). If not interest rates, what would cause the Japanese yen to strengthen and endanger the yen carry trade (YCT)?

This report explains why the yen has behaved as a counter-cyclical (“risk-off”) currency over the past two decades, and why interest rates might not matter going forward.

It also identifies the various forms of the YCT, estimates its size, and deliberates on its drivers and the conditions for its unwinding.

Origins Of Yen Counter- Cyclicality

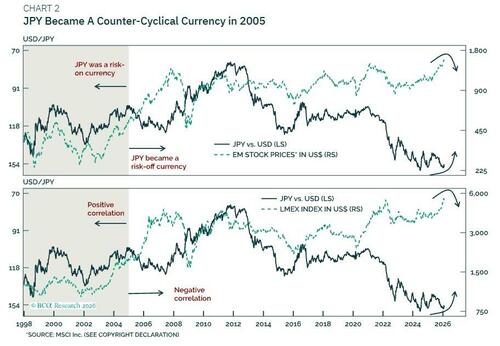

The yen was a pro-cyclical currency until 2005 (Chart 2). Since then, it has become counter-cyclical.

Two main forces drove this paradigm shift:

(1) Japan’s rising income from foreign assets, and

(2) the proliferation of yen carry trades.

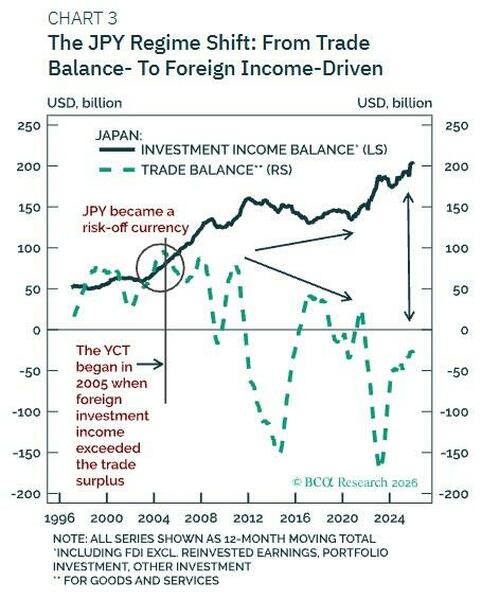

The yen’s transition to a counter-cyclical currency occurred when net foreign income began to exceed the trade surplus (Chart 3). Before this exchange rate regime shift, the trade balance – which was the dominant component of the balance of payments – shaped exchange rate dynamics. When foreign investment income exceeded the trade balance, the currency became driven by Japanese investors’ propensity to repatriate foreign income.

This repatriation intensifies when Japanese investors experience losses on their foreign investments. Hence, the yen appreciates when global volatility rises and risk assets sell off.

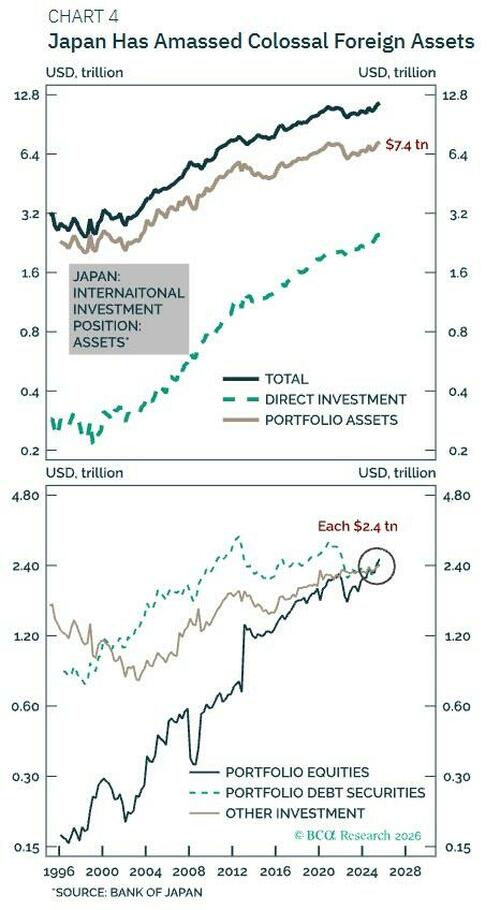

Over the past few decades, Japan has built up a colossal pile ($12 trillion) of foreign assets. Portfolio assets (listed equity and debt securities) and other investments, such as deposits and loans, make up $7.4 trillion of these foreign assets, with the rest comprising foreign direct investment (Chart 4).

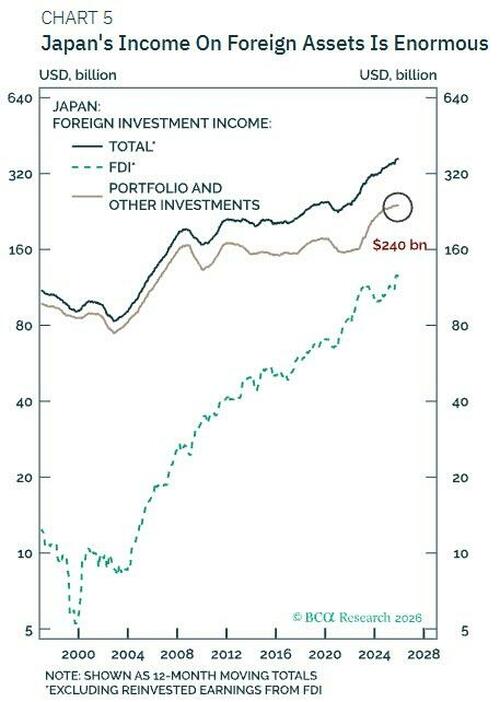

Japanese investors have been earning sizable foreign income on these international assets.

For example, last year the income from these portfolio assets amounted to $240 billion (Chart 5).

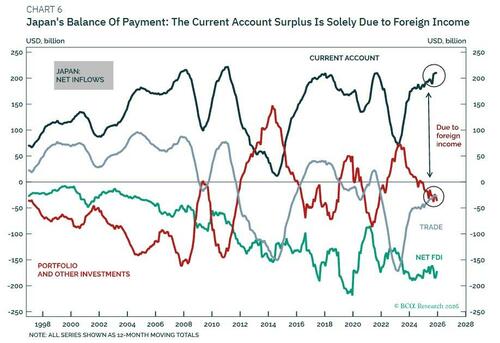

Critically, Japan runs small trade deficits but has a current account surplus of $210 billion (Chart 6).

The gap between the two is due to earned foreign income.

Hence, foreign income flows play a pivotal role in determining exchange rate trends.

The dynamics are as follows: When a larger share of foreign income remains abroad, the yen weakens. On the flip side, when a notable share of foreign income is repatriated, the yen strengthens.

In sum, swings in the yen are often driven by investment decisions by Japanese investors and corporations whether to reinvest or repatriate their foreign income.

These allocation decisions, in turn, largely depend on (1) the global risk environment (global market volatility), and (2) their outlook for the exchange rate. The impact of interest rate differentials is secondary. Bottom Line: A switch in the yen’s drivers from trade dynamics (exports) to foreign income repatriation led to a regime shift in the JPY from pro- to counter-cyclical. In turn, the yen’s strong correlation with global market volatility points to the YCT’s prevalence. The latter then reinforces the yen’s counter-cyclical behavior.

Drivers Of The Yen Carry Trade

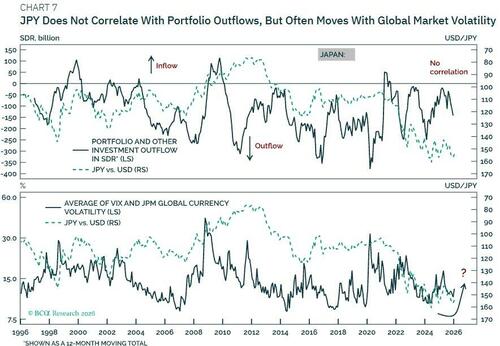

On the one hand, there is little correlation between Japanese foreign portfolio outflows and fluctuations in the JPY (Chart 7, top panel).

On the other hand, as shown in the bottom panel of Chart 7, the yen correlates with global market volatility (we use the average of VIX and JPM global currency volatility indices).

Together, these observations suggest another major hidden force is responsible for the yen’s fluctuation: the yen carry trade.

The YCT can be broadly defined as the practice of borrowing in – or shorting – the JPY to fund purchases of higher-yielding assets.

These strategies benefit from the yield spread and potential capital gains on these assets, but they are exposed to losses if the yen appreciates

YCTs have several components:

1. The prices of “carry” assets: Capital gains/losses on assets that the YCT is used to fund.

2. The exchange rate itself: The JPY’s exchange rate versus the currency that the “carry” asset is denominated in.

3. The carry: The yield differential between the borrowing/funding rate in the Japanese yen and the yield on assets owned/carried.

For the YCT to be profitable, the net aggregate return from all three drivers should meet investors’ expected return.

An analysis of previous yen carry episodes reveals that fluctuations in “carry” asset prices (#1 above) and the yen’s exchange rate (#2 above) were much more important drivers than the carry (#3 above). Intuitively, the “carry” asset price and the exchange rate fluctuations are always greater than the interest rate differentials between Japan and other economies.

Those fluctuations (#1 and #2) define whether investors increase or reduce their exposure to YCTs.

There were three major episodes of YCT unwinding: 2008, 2015-early 2016, and 2020.

Critically, in the three episodes, a drop in “carry” asset prices is what caused the YCT unwinding, not higher policy rates or bond yields in Japan. More specifically

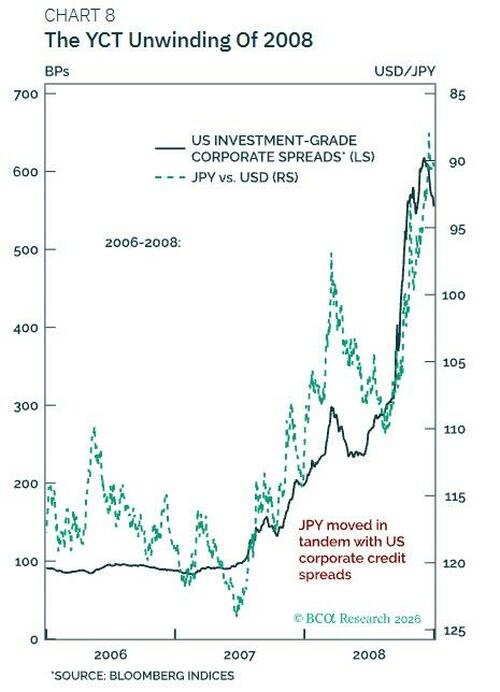

2008: The YCT proliferated in 2005-2007.

Even though Japan’s central bank hiked its policy rate by only 25 basis points from 0.25% in February 2007, YCT unwinding began in late 2007. Hence, in this episode, falling global risk asset prices are what caused the YCT reversal, not a rising cost of carry. The former stemmed from cracks in the US credit system, which ultimately culminated in the Global Financial Crisis in late 2008. Chart 8 demonstrates that the JPY/USD exchange rate moved in tandem with US corporate credit spreads in 2006-2008.

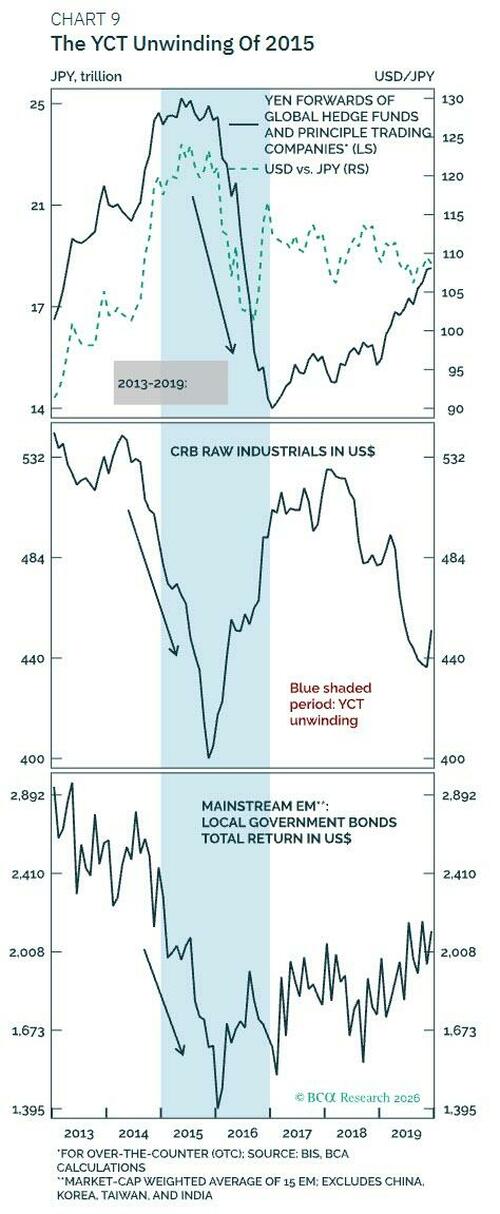

2015: The selloff in EM risk assets led to YCT unwinding.

A major growth slowdown in China, falling commodity prices, and poor fundamentals in EM caused the selloff (Chart 9).

Interestingly, even the BoJ’s massive QE program did not prevent the YCT from unravelling in 2015.

2020: The COVID pandemic selloff also led to a temporary reversal of the YCT in early 2020.

The driver was once again the drop in “carry” asset prices, not rising interest rates in Japan.

Bottom Line: The past three major YCT unwinds followed a drop in “carry” asset prices, not a rise in JPY funding rates.

Our hunch is that the next unwinding case will also be triggered by a combination of a drop in “carry assets” and/or a rebound in the yen. It is impossible to know which will occur first. But they will reinforce each other, resulting in a major reversal of the yen carry trade.

Measuring The Yen Carry Trade

There is no single metric that can adequately capture the scope and scale of the YCT. However, evidence suggests the YCT has proliferated over recent years and that the amounts involved are substantial.

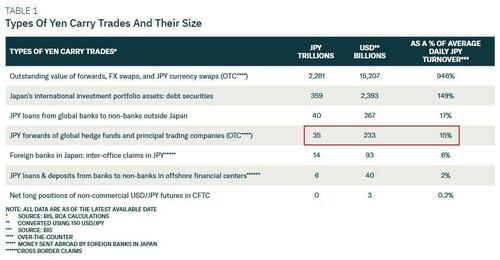

Table 1 puts the potential size of various types of YCT into perspective.

It lists the outstanding amounts in JPY and USD and as a percent of the average daily yen trading turnover.

Notably, in August 2024, Hyun-Song Shin, economic advisor and head of research at the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), cited 40 trillion yen (270 billion USD) for on-balance-sheet yen borrowing and 14 trillion USD for off-balance-sheet Yen swap markets. Both are part of the YCT. Our own estimates are consistent with the ones put forward by Shin.

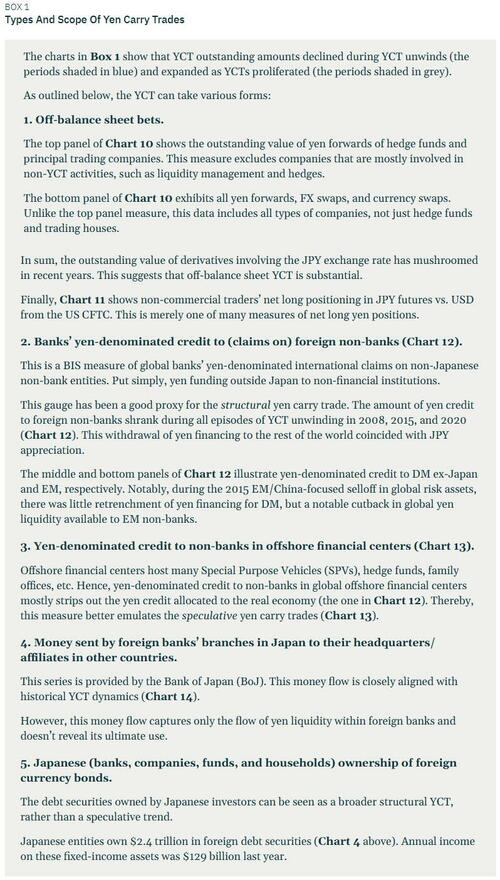

Box 1 discusses the various types of YCT, including off- and on-balance sheet types. Some YCT types are short-term and speculative bets, others are medium- or long-term in nature.

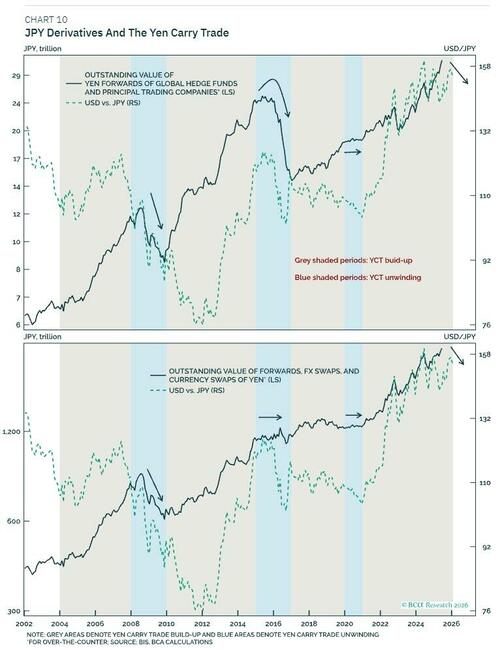

On the whole, the size of YCT is not trivial. Whether it is measured by way of derivatives, yen-denominated lending to entities outside Japan, or Japanese investors’ foreign portfolio assets, the amounts in question are substantial. For example, the outstanding value of yen forwards of global hedge funds and principal trading companies and yen forwards, FX swaps, and currency swaps were 32 trillion yen (or $220 billion) and 2.3 quadrillion yen ($16 trillion), respectively, as of Oct 1, 2025 (Chart 10).

Critically, the massive yen depreciation in recent years has benefited Japanese investors with foreign assets as well as foreign entities with yen-denominated liabilities. Thereby, a major reversal in the JPY exchange rate is likely to produce the opposite effect – a chain reaction that forces a YCT unwinding.

For example, as of September 30, 2025, Japanese insurance companies hedged only 46% of their foreign asset exposure. This is below the peak of 63% in 2020 and the 54% average of the past 15 years. When yen appreciation commences, insurance companies will rush to increase their hedge ratio, bolstering the yen’s rally.

Bottom Line: The size of the YCT is considerable. Once global risk assets begin selling off (i.e., global market volatility rises) or the yen starts appreciating rapidly, Japanese entities will respond with one or more of the following:

(1) reduce their new investments abroad,

(2) repatriate income on foreign assets,

(3) repatriate some of their foreign assets, and/or

(4) hedge currency risk on their international assets.

This will reinforce the yen’s appreciation and lead to an unwinding of the YCT worldwide.

Investment Implications

The yen carry trade’s risk-reward profile is poor. But the timing of its reversal is uncertain.

Many entities have amassed non-trivial off- and on-balance sheet exposure and, hence, have greatly benefited from yen depreciation.

When the yen begins appreciating, the move will be sizable because of the proliferation of YCT, i.e., large amounts involved.

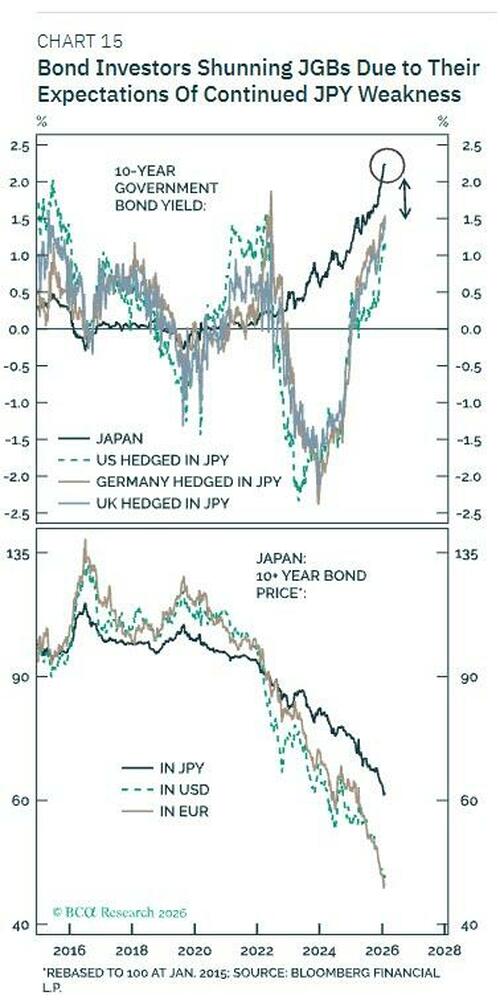

Critically, 10-year Japanese bonds currently offer higher yields than hedged 10-year bonds in the US, the UK, and Germany (Chart 15).

This suggests that, by opting for lower yields on foreign bonds versus domestic bonds on a currency-hedged basis, Japanese fixed-income investors are positioned for continued yen weakness.

When and as Japanese fixed-income investors change their outlook for the exchange rate, their net outflows will diminish, and they will hedge foreign currency risk on their international assets.

This will produce a major yen appreciation.

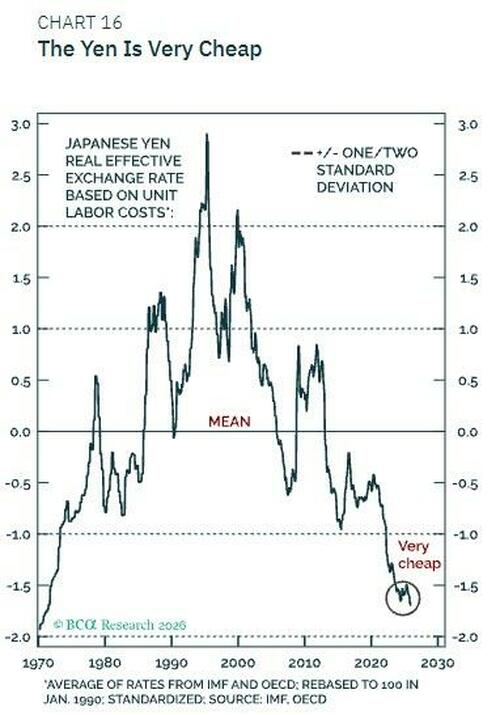

Needless to say, the trade-weighted yen is very cheap. Its Real Effective Exchange Rate – based unit labor costs – is at its lowest in over 50 years (Chart 16).

We, at BCA’s Emerging Markets Strategy team, are bearish on the US dollar and believe that it will become pro-cyclical.

If the greenback depreciates amid a global risk asset selloff, the yen could rally significantly against the US dollar.

This would be a harbinger of YCT unwinding.

Last week, we published a report titled Little Dry Powder On The Sidelines, arguing that cash on the sidelines as a share of equity market cap is at a record low in the US, and very low in the Euro Area, the UK, and Japan. This is consistent with both global risk-on positioning and the YCT being overstretched.

As to global equity portfolios, we recommend overweighting Japan and Europe, maintaining neutral weighting on EM, and underweighting the US (mostly driven by our currency views).

In currency markets, medium- and long- term investors should consider going long the JPY versus the US dollar. This is in addition to our long positions in KRW and TWD, which were initiated on January 15 and 29, 2026, respectively. We have been shorting IDR, PHP, and ZAR versus an equal-weighted basket of EUR, JPY, and USD. Today, we recommend removing the USD from the long leg of these positions. Continue shorting IDR, PHP, and ZAR versus an equal-weight basket of the Euro and Japanese yen.