Why The Global Asset Boom Is In China's Hands

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

Surging money growth and a weak economy are generating trillions of dollars of excess liquidity in China which is leaking abroad, inflating global asset prices. A strong Chinese recovery, therefore, could eventually be a problem for markets.

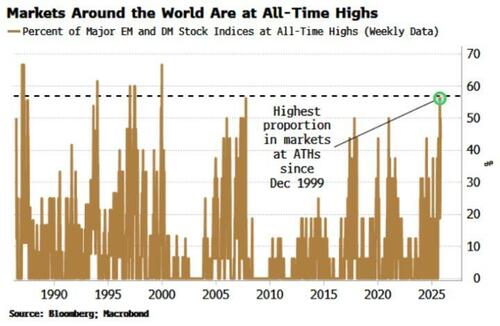

Stocks are wobbling today, but that does not detract from the bigger picture that they have been sailing to all-time highs around the world. The S&P, the Nasdaq, the FTSE, the Nikkei, the Kospi, the Bovespa and more are trading very near record peaks along with, until very recently, gold. No single cause – a resilient US economy, artificial intelligence, a trade truce – can adequately explain why this is. The missing piece is China.

China’s misfortune is a gift to markets around the world. The country’s economic growth continues to falter even after the rapid rise in money growth seen this year. But that is leading to more capital illicitly leaving China with greater urgency, and flooding into global asset markets. You have to go back to 1999 to see a larger proportion of global stock markets simultaneously making all-time highs.

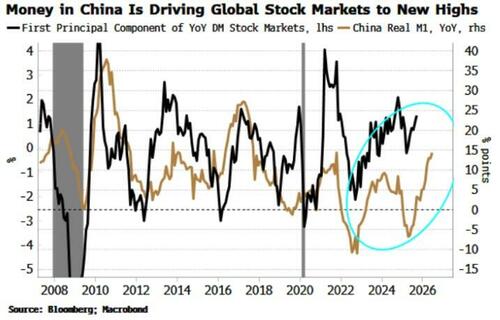

Conventionally, money in China is seen as better for the global economy than global asset markets. But that is not really the case, with the turns up and down of real M1 closely corresponding to those of global stocks.

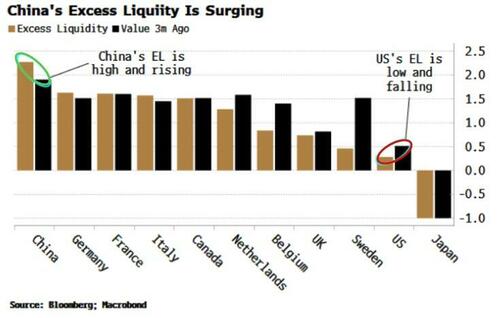

Such giddy asset markets would normally be accompanied by surging G10 excess liquidity, the difference between real money growth and economic growth. But the first has fallen relative to the second, leaving less liquidity that’s surplus to the real economy and therefore available to boost markets.

Yet several things are conspiring to markedly boost and transmit global excess liquidity:

-

A surge in money growth in China

-

Persistently soft economic growth and deflation that is failing so far to react strongly to stimulus

-

Lack of opportunities for capital in the domestic market

-

The weak economy leading to an increase in unofficial hot money outflows from China

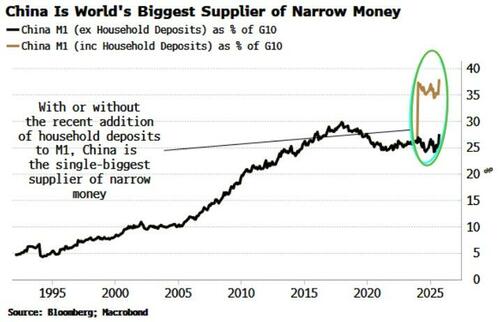

As covered previously, narrow money growth in China has accelerated this year, driven by a surge in the demand deposits of corporates.

But here’s the kicker.

It’s precisely because the Chinese economy remains weak and in deflation that the massive rise in money growth is way in excess to the needs of the domestic economy. China’s contribution to global excess liquidity is now higher than any other country’s, and significantly more than the US’s.

For example, if M1 is growing at 5% a year, and growth and inflation are at 2% each, that puts excess liquidity at 1%. But in China’s case we have deflation. M1 is growing at 7.2%, growth is stated at 4.8% and PPI is negative 2.3%. That means excess liquidity is 3.7%, yet it’s probably even higher as other measures of growth, such as the Li Keqiang index, suggest GDP is actually less than 4.8%

And the numbers we are talking about are vast. M1 in China (including household deposits, which were recently added) is $16 trillion, twice as much as the $8 trillion for the US (excluding saving deposits), and almost the $18 trillion for the rest of G10. Narrow money in China is thus almost 40% of the global total.

That’s a lot of liquidity looking for better returns.

Unfortunately, there are limited options at home.

Bond yields in China are low, with the 10-year yield only offering 1.8% (although deflation means the real return is higher).

The property market continues to struggle. House prices are flat, new floor space started is contracting, growth in real estate transactions keeps falling and total mortgage supply is declining.

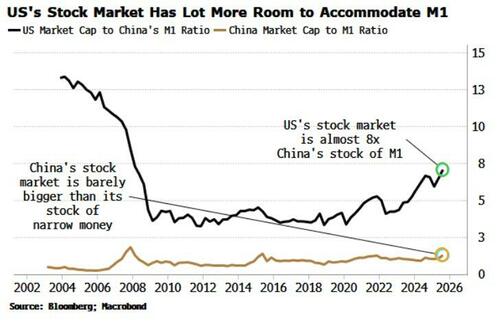

And the stock market is too small, with its total market cap barely larger than the stock of narrow money, versus a ratio of almost eight times in the US.

It’s no surprise, therefore, that more capital is leaving China in hot-money flows circumventing the nominally closed capital account.

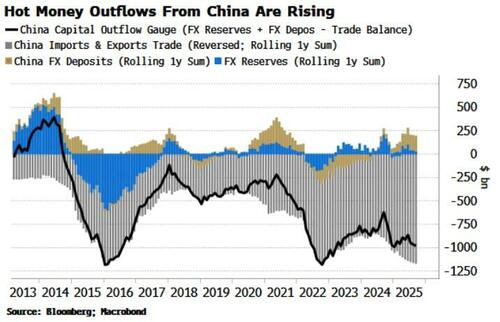

To gauge the extent of unofficial outflows, we can look at the difference between the trade surplus, and official reserves and bank FX deposits. In a closed capital account, all proceeds from trade surpluses should end up as FX reserves or deposits at the central or commercial banks. Thus any discrepancy between the two gives a proxy for capital that has leaked abroad.

Despite tariffs, China’s trade surplus has continued to soar this year reaching a record high of almost $1.2 trillion. Yet FX reserves and deposits have not risen by much at all. As the chart below shows, that could mean as much $1 trillion a year is leaving China surreptitiously.

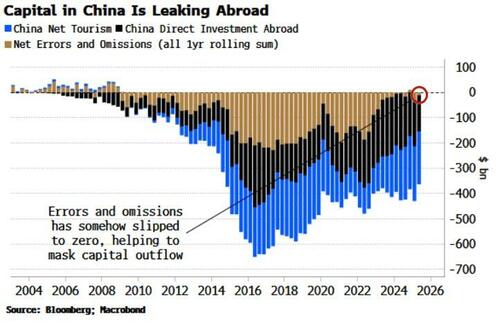

This might be a problem for policymakers in China, as can be inferred by looking at the capital and current accounts.

Brad Setser of the Council on Foreign Relations has persistently pointed out that the trade surplus as taken from the current account has fallen to about half the surplus based on the customs data (I use the latter in the above chart). That followed an opaque methodology change in the balance-of-payments accounts.

Miraculously, this year the errors and omissions in the BOP data has gone to zero. Such errors are the difference between the current and the capital and financial accounts, which should tally and is an indicator of illicit capital outflow. To get it to zero in an economy with such a massive balance of payments, and to do so very quickly, stretches credulity.

As Setser suggests, narrowing the current-account surplus reduces the errors and omissions and brushes under the carpet rising capital outflows that could be “embarrassing” to the Chinese.

But how are capital controls being circumvented?

There are signs the usual tricks are being employed.

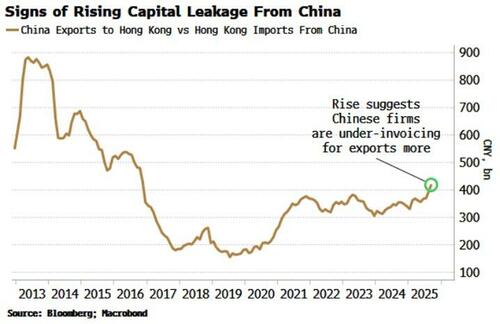

One of the simplest, which was heavily used in the 2010s until the authorities started to clamp down on it, is “trade mis-voicing”.

Mainly this is through under-invoicing for exports. As this practice became rife in the 2010s, the difference between exports from China to Hong Kong and imports from China as recorded in Hong Kong surged. It is rising again now.

If this practice looks like it’s happening for exports to Hong Kong, it’s surely happening elsewhere too, along with the employ of other methods to clandestinely export capital.

Ironically, given it’s the combination of strong stimulus and a lacklustre economy that’s leading to such high excess liquidity and its egress, a strong recovery in China could be a problem for global risk assets. Until then though, stock markets globally, at least outside of China, can go on making new highs.