The Yield Curve Does This When The Fed Makes An Emergency Cut

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

The Federal Reserve’s interest-rate cut in September was preceded by a rare move in the risk-neutral yield curve that, in recent decades, has almost always only occurred around unscheduled meetings and before significant moves in monetary policy.

If history is any guide, that suggests at least one of two things:

1) the market believes the Fed’s resumption of rate cuts in September was a policy mistake; and

2) the move lower in rates likely has a lot further to go.

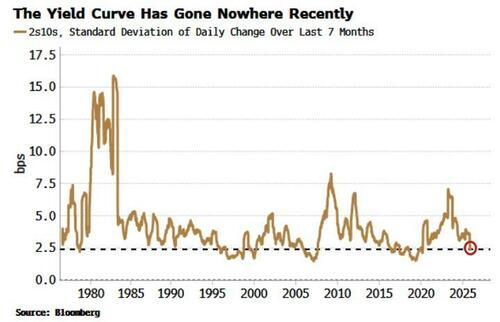

This is not a normal cutting cycle. Since the aftermath of President Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariff announcements, the 2s10s curve has been almost still compared to history. The volatility of its daily move has been lower only a handful of times over the past 50 years.

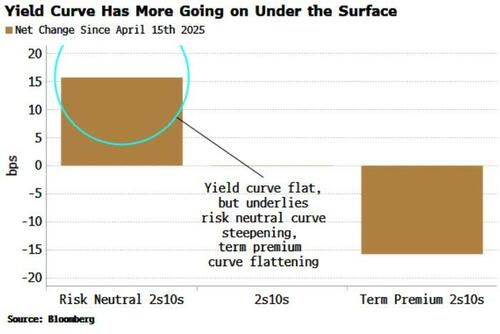

When we disaggregate the move in the yield curve, however, we find something more unusual. The net move in the 2s10s curve since April 15 (when the curve settled down after the initial tariff-driven volatility) has been near zero. However, it underlies a rise in the 2s10s term premium curve versus the 2s10s risk-neutral curve (using ACM term premium; as a reminder, Treasury Yield = Risk-Neutral Rate + Term Premium).

That’s happened less than 10% of the time over the last half a decade. But rarer again is how the risk-neutral curve steepened: the two-year risk-neutral rate fell more than the 10-year rate in a bull steepening, something that’s only happened three other times, to the same magnitude, in the last 35 years.

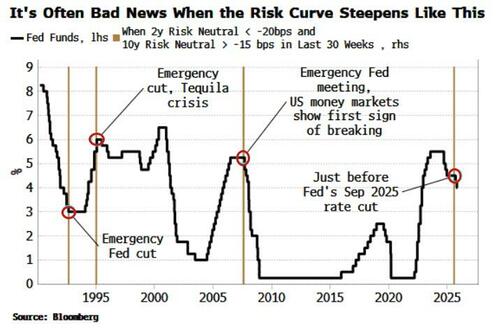

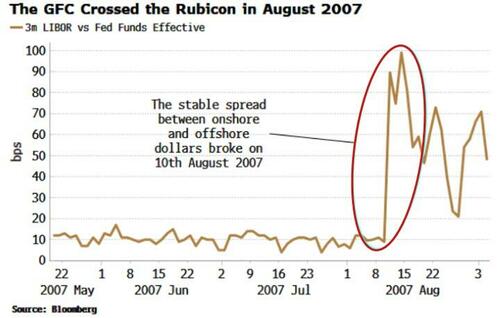

As we can see from the chart above, those occurrences were not random. The last was on August 9, 2007, literally the day before the first clear signs that something was seriously amiss in the money markets, as the implicit parity between onshore and offshore dollars broke.

The market sensed the Fed was not taking the situation seriously enough. The bank held unscheduled conference calls on August 10 and 17 in 2007, acknowledging the situation and offering verbal support, but declining to do anything concrete. The market clearly thought the Fed should have already been aggressively cutting rates, which it did not start doing until mid-September.

Before that, the risk-neutral curve bull steepened as it did this year on January 13, 1995. This was the exact day the Fed held an emergency meeting to cut rates in response to the collapse of the Mexican peso, which set off what became known as the Tequila Crisis.

In the end, the Fed did not significantly reduce rates, but at the time the market sensed a potentially acute problem, and rapidly adjusted the short-term risk-neutral rate lower.

Before 1995, we have the unscheduled Fed cut on September 4, 1992, the last rate reduction of a steep cutting cycle that began in 1989, after the Fed was satisfied it had got inflation under control.

What do the above instances have in common and why did the risk-neutral curve bull steepen as it did?

All involved unscheduled Fed meetings that resulted in a rate cut, or pointed strongly in a bond bullish direction. In each case, the market took down the near-term risk-neutral rate more than the long-term one – which, as noted above, is rare – as it likely anticipated that the move would be temporary.

The risk-neutral curve used to bull steepen much more frequently prior to the 1990s. It wasn’t until then that Fed Governor Alan Greenspan finally completed his predecessor’s work in containing inflation expectations and setting the stage for the NICE (non-inflationary continuous expansion) decades.

Which brings us to the most recent instance, happening not long before the Fed’s September cut of this year. This was not an unscheduled meeting, but it was different in one respect: enormous pressure was being placed on the FOMC, and Chair Jerome Powell in particular, to cut rates, despite multiple signs that policy in many respects was not especially tight.

President Trump has made his views plain he would like to remake the FOMC in his own low-rate-cutting image. The addition of Stephen Miran to the FOMC was a clear step in that direction, with the new appointee willing to challenge the group consensus and consistently call for rate cuts.

As Jim Bianco of Bianco Research suggests, the addition of Miran is breaking the stranglehold the Chair has traditionally had over the FOMC, with dissents rare and full consensus the norm.

That’s a positive benefit if the Fed shifts to more independent voices, willing to vote against the Chair, moving the FOMC toward other central banks such as the BOE, where split decisions are common. But it also leaves the Fed more exposed to fiscal interference if the White House is able to install more Mirans on the committee, or a more pliable Chair.

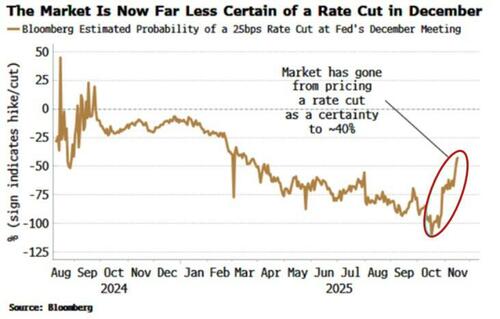

Market expectations for the Fed cutting at its December meeting have fallen from 100% to under 40% despite no new significant economic data nor comments from Powell. This is not necessarily a bad thing – introducing some uncertainty back into markets will quell some of their more exuberant tendencies.

But the bull steepening of the risk-neutral curve suggests something is amiss. Similar to the bull steepening in August 2007, when the market sensed a policy mistake by omission, this time the market is hinting at a policy mistake by commission. Given the rate cut was not an emergency, the decline in the two-year risk-neutral rate by more than the 10-year rate suggests a concern about inflation.

And no wonder, with a $2 trillion dollar fiscal deficit, a central bank seeing its independence winnowed away and CPI persistently above target, inflation is likely going to be around for some time. Regardless, a compromised Fed may just keep cutting rates, and the lesser move in the 10-year risk-neutral rate implies that the market thinks this will ultimately stoke inflation further, forcing the Fed to hike rates eventually.

So while the September cut was not an emergency move in an acute sense, we may be witnessing a slow-motion car crash. If it comes to pass, we can’t say the risk-neutral curve didn’t warn us.