Borrowing is America’s Past, Austerity its Future

“The economically efficient system of a dollar standard may serve the cosmopolitan interest in a national frame. Its demands on world sophistication are excessive.”

— Charles Kindleberger, 1981

How Borrowing Became America’s Weakness

Contents (580 words)

- Developed Market Shows Emerging Market Behavior

- Two Ways Out: Adjustment or Crisis

- Tariffs Won’t Fix the Twin Deficits

- From Central Banks to Private Capital

- Reserve Currency, Shrinking Privilege

- Strategic Implications

Summary

Authored by GoldFix, ZH Edit

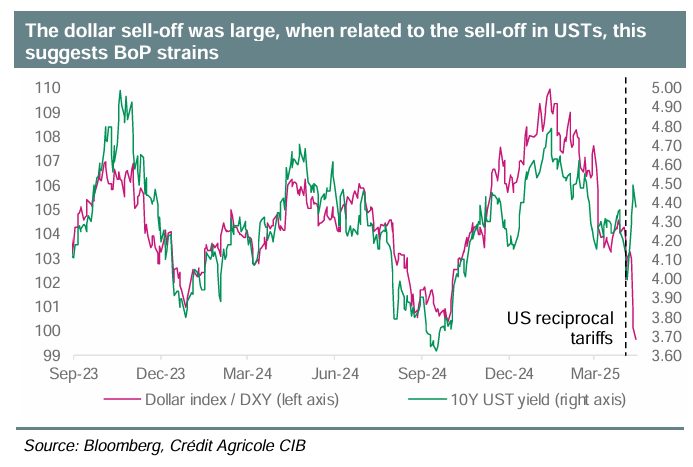

A fracture in the traditional U.S. macroeconomic model is now visible to markets. Bond yields are rising, but the dollar is falling—a pattern typically associated with emerging markets in crisis. The recent tariff escalation has triggered something deeper: a genuine external financing strain. We summarily look at the CA report detailing how that happened, why it matters, and what could come next.

1. A Developed Market Shows Emerging Market Behavior

In a normal macro environment, higher bond yields mean a stronger currency. That rule broke down last week. Yields on U.S. Treasuries rose, but the dollar sold off sharply.

When higher returns no longer attract capital, the issue isn’t return—it’s trust. This is exactly how investors treat emerging markets under stress.

This divergence reflects capital flight—a rotation out of U.S. assets despite better nominal returns. For the U.S., which has long relied on global inflows, that’s not just a market quirk—it’s a shift in regime.

2. Two Ways Out: Adjustment or Crisis

Countries in balance-of-payments (BoP) stress have two options:

- Internal Adjustment (Fiscal contraction or policy credibility)

- Currency Crisis (Devaluation and loss of confidence)

The U.S. hasn’t been externally disciplined since the Volcker era. But this time, even the hint of BoP instability is moving global capital.

There are signs of policy moderation already coming out of Washington. Still, the fact that “external solvency” is being questioned at all is telling.

3. Tariffs Won’t Fix the Twin Deficits

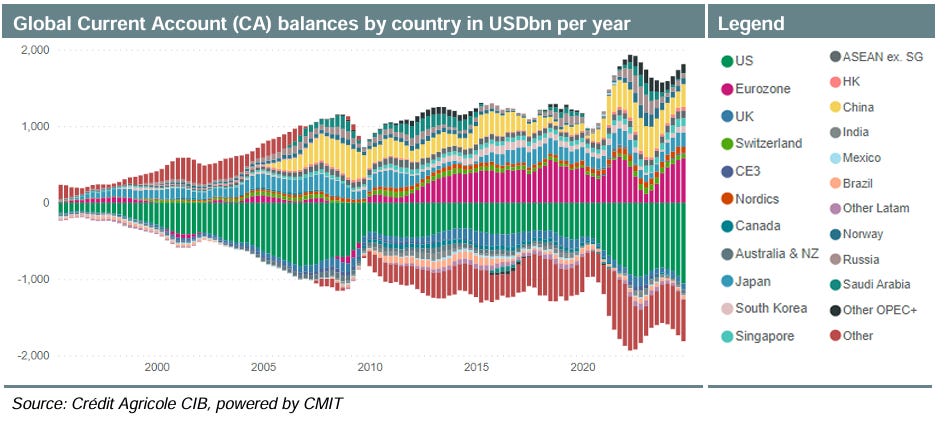

Trump’s tariffs target bilateral trade gaps. But the current account deficit reflects structural imbalances between domestic savings and investment, not trade alone.

The U.S. doesn’t have a trade problem. It has a savings problem—and a spending addiction.

As long as the fiscal deficit (currently ~6% of GDP) persists, so will the current account gap—and so will America’s need for foreign financing.

4. From Central Banks to Private Capital

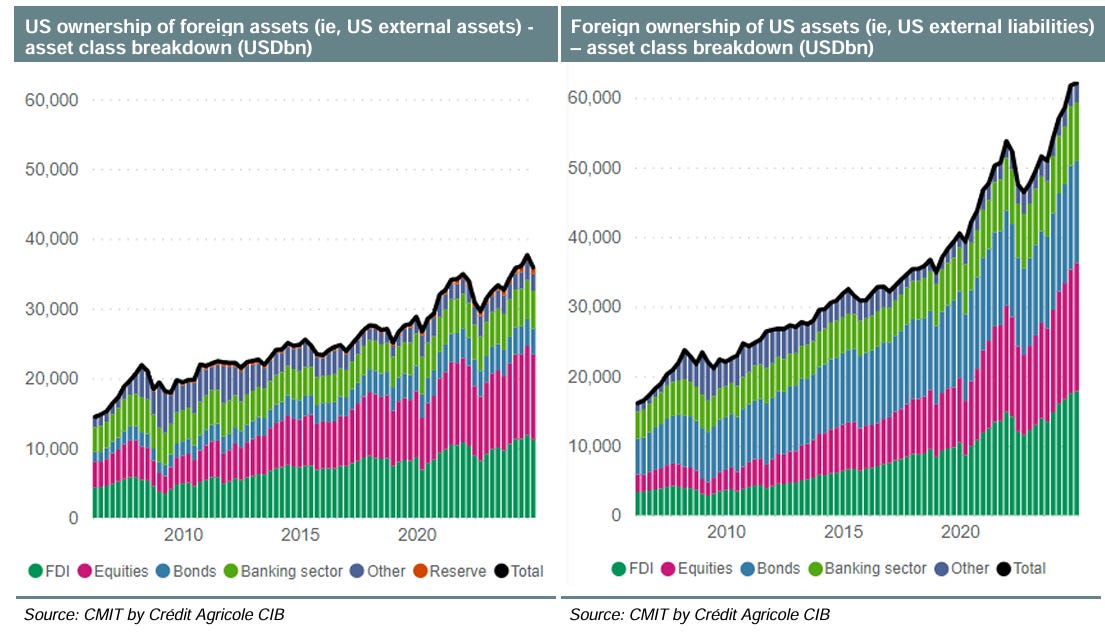

The composition of U.S. external financing has shifted

Foreign central banks are no longer the buyers they once were. The U.S. is now dependent on private capital, which is more volatile and procyclical.

The U.S. used to be financed by policymakers. Now it’s financed by portfolio managers. That makes everything more fragile.

5. Reserve Currency, Shrinking Privilege

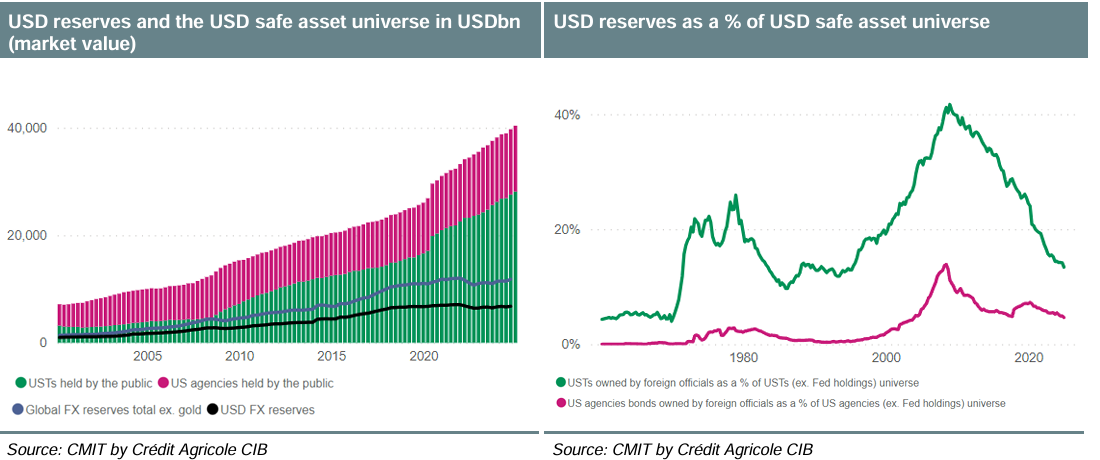

The dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency has long insulated the U.S. from external pressures. But the marginal demand for dollar assets is now cyclical, not structural.

The global demand for Treasuries isn’t growing. It’s just being rolled over. There’s no automatic bid anymore. That matters.

If foreign capital dries up, either spending must fall, or the dollar must adjust. Either path brings volatility—and potential political crisis.

6. Strategic Implications

- Gold Is Signaling: Capital rotation out of the dollar strengthens the case for gold as a strategic hedge—not a speculative play.

- Policy Risk Is Now Market Risk: Tariff escalation can now trigger BoP reactions. U.S. trade policy is being priced like EM policy.

- Imported Austerity: If investors demand deficit reduction, America may face foreign-imposed fiscal constraints without domestic consent.

Continues here

Free Posts To Your Mailbox