Currency Regime Change: Is Dollar Dominance Dead?

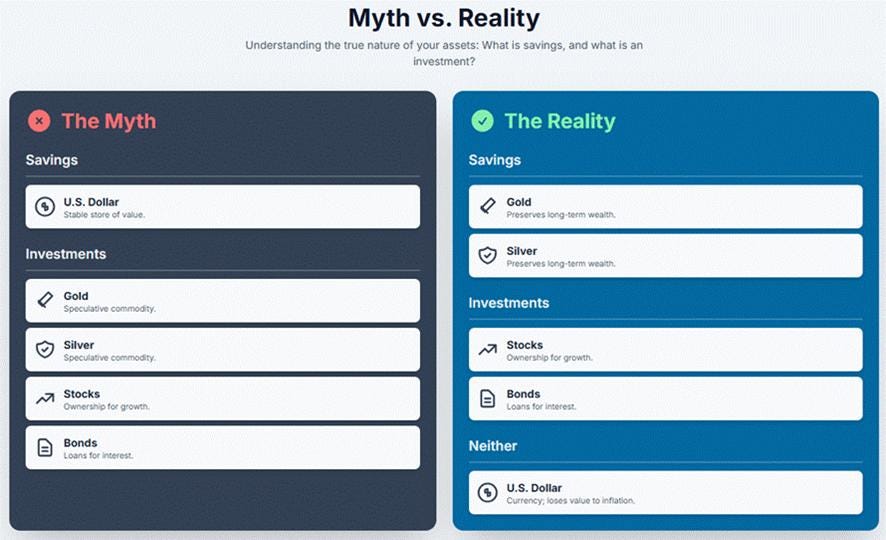

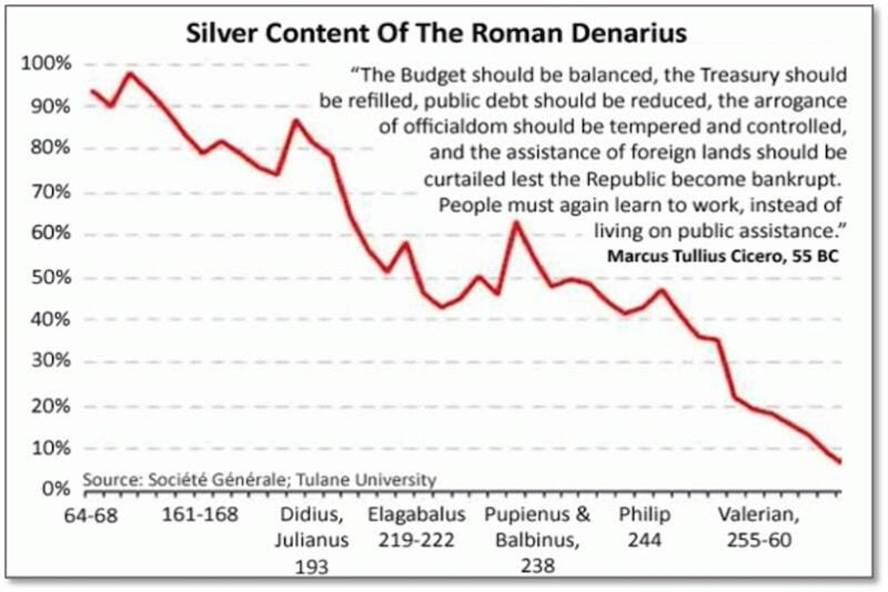

The sages who studied the rise and fall of kingdoms would chuckle today, for the lesson is ancient: money is the hard-earned fruit of labor, while currency is merely the paper promise that it still tastes good. Money—like gold and silver—is the crystallized effort of real work and real scarcity. Currency, however, is its excitable younger cousin: useful for trade, but spoiled the moment rulers discover the printing press. Money is the idea; currency is the performance. One endures through dynasties, the other ages like milk whenever governments “manage” it too enthusiastically. As Master Kong might say: “He who thinks he is saving money, but saves only currency, will one day learn the difference the hard way.” In short, money keeps its virtue; currency keeps asking us to believe it still has some.

You save money; you spend currency.

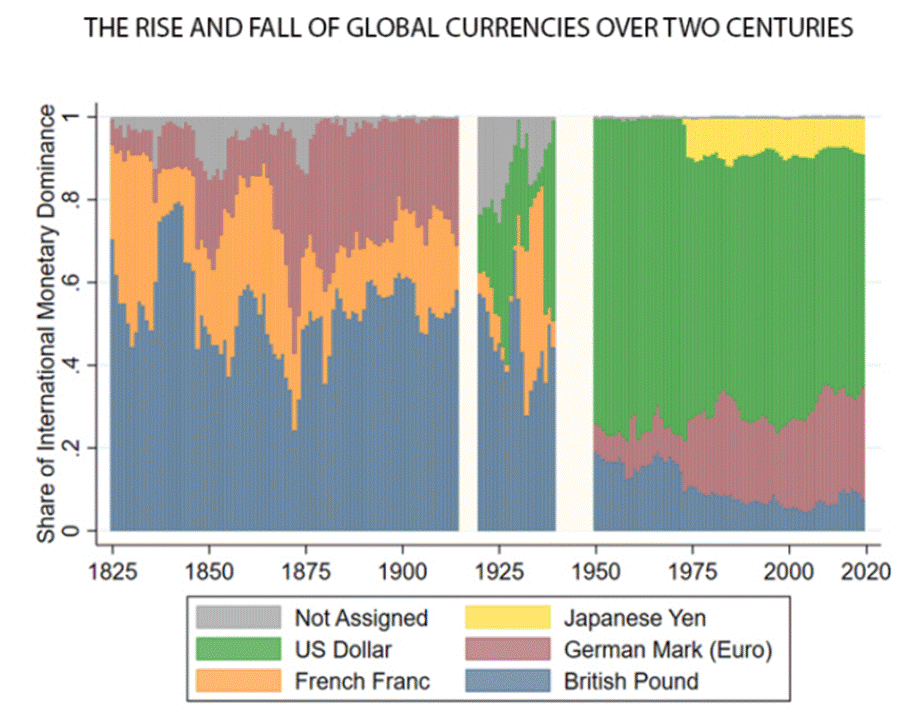

Across history, global monetary power has shifted with the rise and fall of empires. Ancient economies were anchored by precious-metal coins like Rome’s denarius and China’s tael, whose value stemmed from the metals themselves. The Renaissance ushered in the era of the florin and guilder, as European trade flourished on hard currency. By the 19th century, Britain’s pound sterling dominated global finance, supported by industrial strength and naval supremacy. The 20th century crowned the U.S. dollar, institutionalized through Bretton Woods and later entrenched as the world’s reserve currency, central to global trade, commodities, and payments. In every era, currency dominance has been less about the metal or paper—and more about the geopolitical and economic power standing behind it.

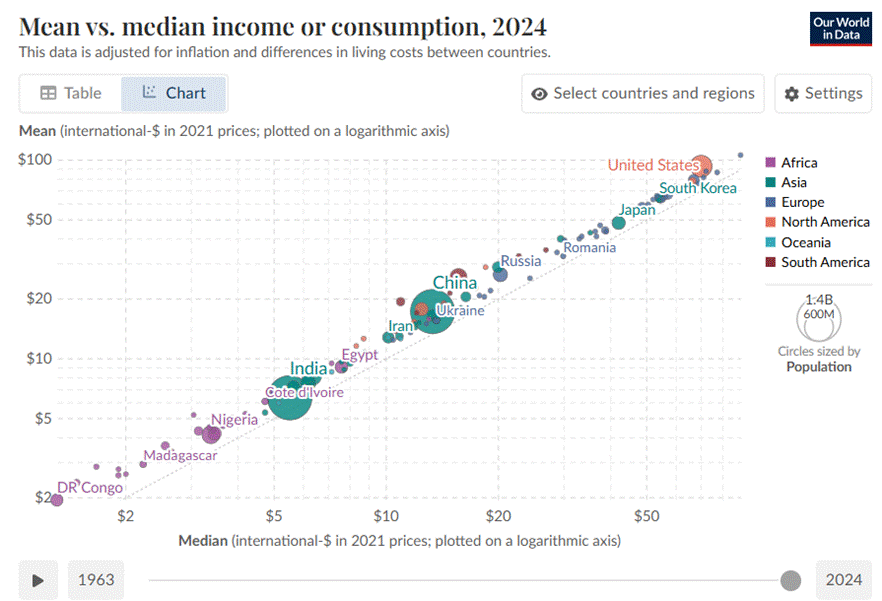

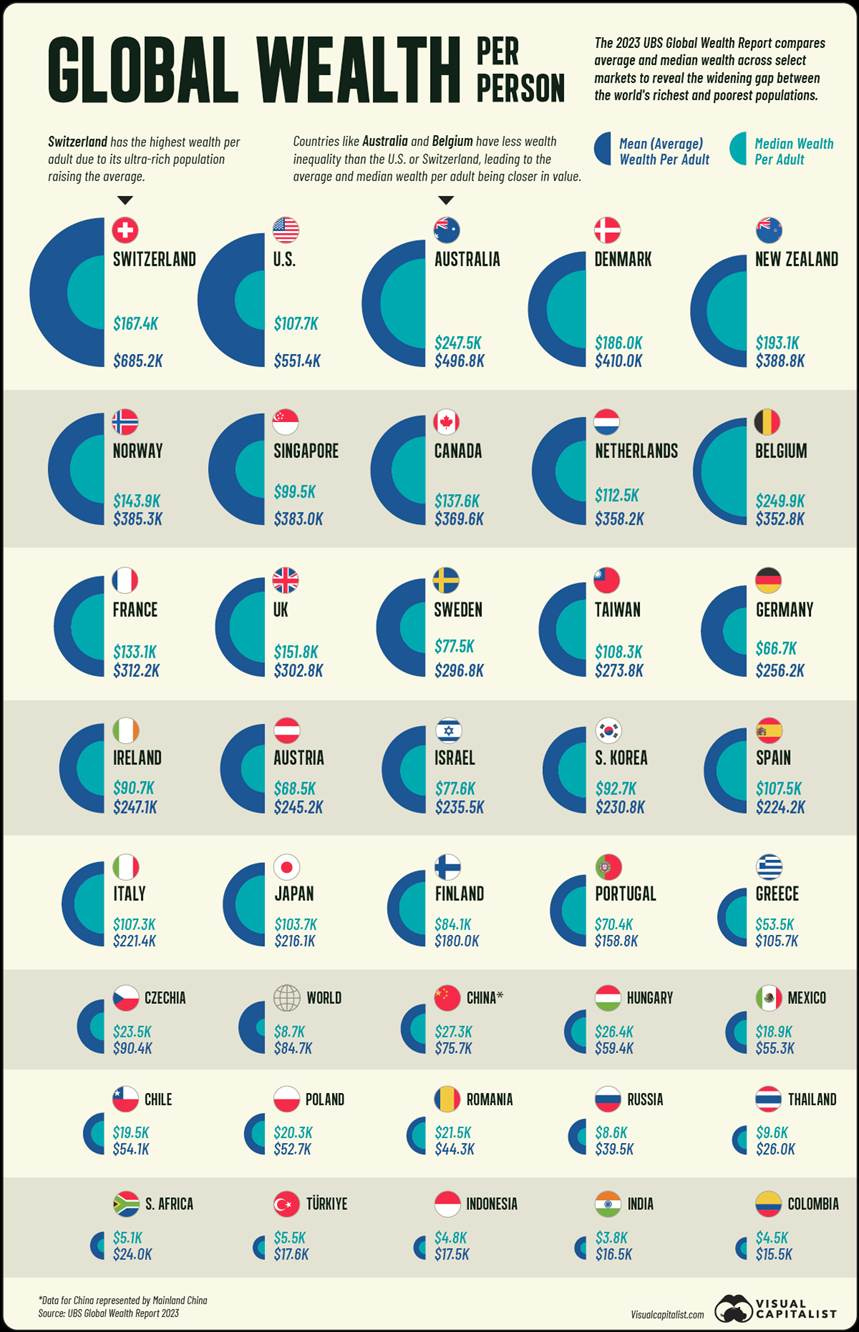

The United States holds only 5% of the world’s people, yet somehow manages to inhale 25% of the world’s consumption. As the Master might say, “When one household eats like five, the neighbors will surely notice.” Americans burn through a quarter of global oil, nearly a third of the world’s aluminum, almost a quarter of all coal, and a healthy share of copper. No wonder nations line up at America’s gate, eager to trade—who wouldn’t serve a customer with such an appetite? Europe, though more populous, spends with the restraint of a scholar-official counting his brushstrokes. The EU’s collective consumer spending reached $9.6 trillion in 2023, which works out to about $21,300 per person—falling further in 2024. Meanwhile, the average American spends roughly $51,500, proving that while Europeans may savor life, Americans certainly buy it.China’s middle class is rising steadily, like bamboo after spring rain, and may one day surpass America in size. But for now, the average Chinese consumer spends about $4,800 a year. Their population rivals Europe and the U.S. combined, but the wallet has yet to match the ambition. Even after adjusting for purchasing power, U.S. per-capita spending remains seven times higher. As Confucius might conclude: “Prosperity grows in its own time. But appetite—ah, that grows fastest of all.”

Private consumption has made up more than half of Europe’s GDP for nearly three decades, meaning the continent runs on shoppers, not soldiers. So when inflation and uncertainty make Europeans tighten their wallets, the whole economy catches a cold—sometimes from nothing more than a sneeze in consumer spending. As for geopolitics, history shows nations always pick fights when they need funding. Russia sits on the world’s richest pile of natural resources, which makes it look a bit like Manchuria in 1931—and explains why some in Europe eye it like a bargain sale. Germany still swears by mercantilism—export everything, consume little, and hope the world keeps buying. It has given Europe a manufacturing powerhouse, but it’s not the model China is using to rise as the next global financial center. Germany’s lingering fear of inflation keeps taxes high and spending cautious, a habit born from World War I scars. America, by contrast, got rich by buying everything in sight—and letting the world rush in to sell to them. Italy, meanwhile, quietly reminds everyone that wealth and GDP aren’t the same thing. Despite having half of Germany’s GDP, Italian households often come out richer on paper. A few years ago, Italians and Spaniards were even wealthier than Germans, despite Germany’s economic bragging rights. China has noticed. It’s slowly shifting toward a U.S.-style consumer economy. Give it 15–20 years, and nations may be lining up to sell to Beijing the way they once lined up for American shoppers.

History isn’t a neat march of “progress,” nor is it the random chaos some academics insist it is. If physics has space-time, economics has… well, a lot of people pretending it does. Einstein gave us Special Relativity; economists can barely agree on what happened last quarter. You probably remember the classic train example: toss a ball at 10 mph on a train moving at 50 mph, and someone on the platform sees 60 mph. Simple. That’s Galilean spacetime. But Einstein ruined the fun by pointing out that this logic collapses near the speed of light—because, inconveniently, light refuses to speed up or slow down no matter who’s watching.

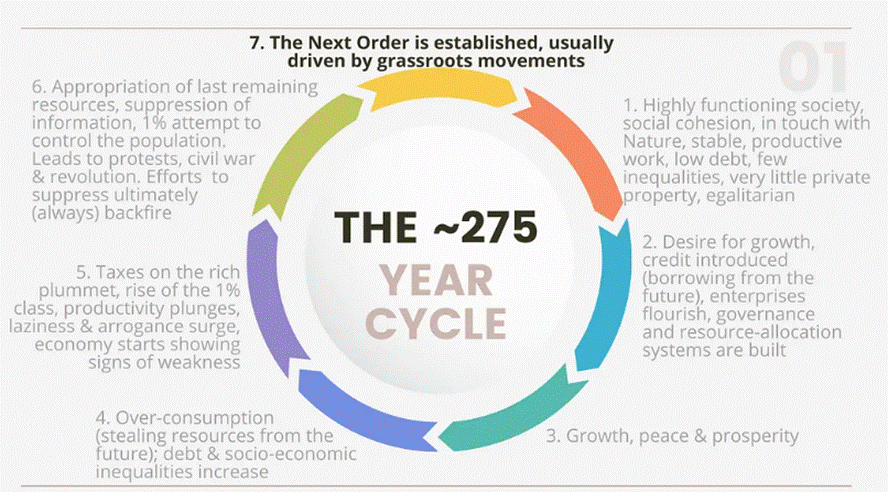

So physicists ditched absolute space and absolute time. Economists, meanwhile, still argue about inflation like medieval scholars debating angels on a pin. Human societies also follow their own strange “relativity.” Empires rise, fall, and occasionally trip over their own egos—not because of cartoon villains or grand ideologies, but because the same cycle keeps repeating. And if you look closely at the data, one pattern stands out: big wars tend to show up only after governments get big enough to afford them.

https://medium.com/society4/part-1-the-changing-world-order-492f91173efc

The foreign exchange market is the heartbeat of global finance — a real-time referendum on government credibility, debt sustainability, and geopolitical stability.

Every currency, from the dollar to the yuan, captures capital in motion. What we’re witnessing now is more than shifting rates or reserves; it’s a shift in confidence itself, echoing the same cyclical transitions that have shaped empires for centuries. With nearly $7.5 trillion trading daily, FX is the world’s true “vote of confidence” market. Politicians legislate and central banks intervene, but capital moves only where it feels secure. It always has — from Rome to Venice, Amsterdam to London, and ultimately to New York. No empire has ever escaped this cycle.

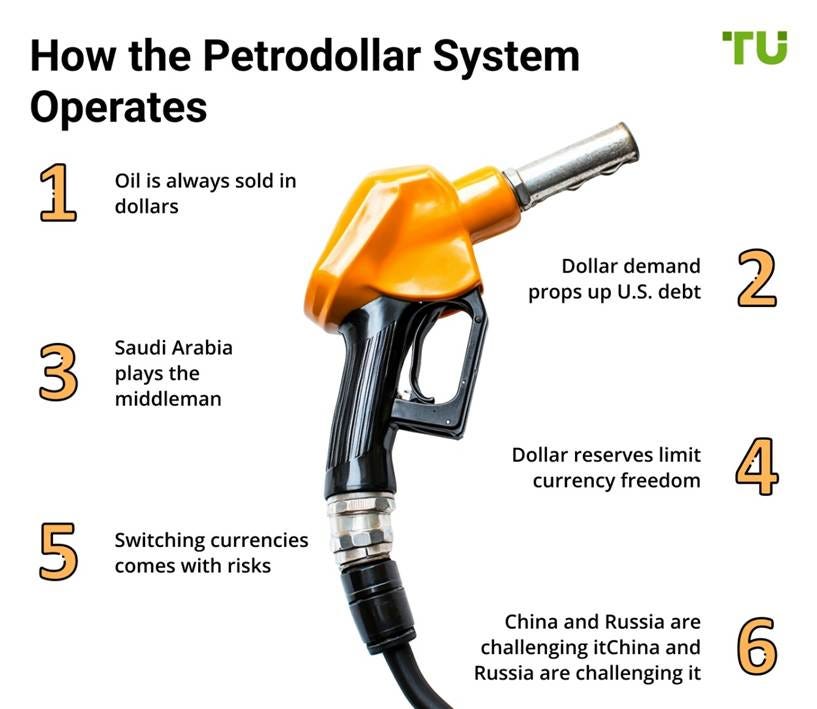

The Petrodollar wasn’t born from economic brilliance—it was born because Washington panicked during the 1973–74 oil embargo and Nixon didn’t want to preside over a country running out of gasoline and excuses. So he sent Treasury Secretary Bill Simon to Saudi Arabia with the subtle instruction: “Come back with a deal or don’t come back.” After a marathon of diplomacy fueled by more whisky than policy memos, the U.S. got Saudi Arabia to price oil exclusively in dollars. Voilà: the Petrodollar—an arrangement that let America treat trade deficits like a teenager treats their parents’ credit card. But the mythology surrounding this deal misses the real point: the dollar isn’t dominant because oil is priced in it; it’s dominant because capital trusts U.S. markets more than anything else on the planet. Even if oil switched to euros tomorrow, exporters would still park their money in dollars. The “Petrodollar” makes a great geopolitical ghost story, but the real engine of dollar supremacy is simple: confidence, liquidity, and the lack of a credible alternative.

https://tradersunion.com/currencies/forecast/oil/petrodollar-agreement/

In the 1970s, Eurodollars—U.S. dollars lounging offshore in European banks—became the fuel for emerging-market megaprojects, including Northern Brazil’s grand hydro dreams. Cheap dollar loans powered the Tucuruí Dam, and when bankers realised there wasn’t enough electricity demand to justify it, they simply financed aluminium smelters too. Problem solved: build the power plant and the energy-guzzling industry to soak it up.

Meanwhile, David Spiro’s Hidden Hand of American Hegemony argues that Treasury Secretary Bill Simon didn’t stumble into the petrodollar deal in a Jeddah whisky fog—he executed it like the ex-Salomon bond trader he was. In exchange for U.S. political and military babysitting of the Saudi regime, Simon got the Kingdom to price all its oil in dollars and secretly recycle its surpluses into U.S. Treasuries via the Cayman Islands. One handshake later, the arrangement quietly still holding for more than 50 years. But the Saudis weren’t keen on keeping all their rainy-day money in Treasuries—too much risk of being labelled monopolists or, worse, waking up to find the funds “patriotically repurposed.” So they deposited mountains of dollars in London, Paris, and Geneva offshore banks. Those banks, paying double-digit interest rates, desperately needed to put the cash to work—and naturally lent it back out in the same currency they got it in: U.S. dollars. They poured money into commodity finance, trade finance, and emerging-market infrastructure—anything collateralised, revolving, or remotely plausible. As demand for these loans exploded in the late ’70s, European banks effectively financed the entire industrialisation of Emerging Markets with Eurodollars, proving once again that if the world gives bankers a river of dollars, they will build a dam—and a smelter—to justify it.

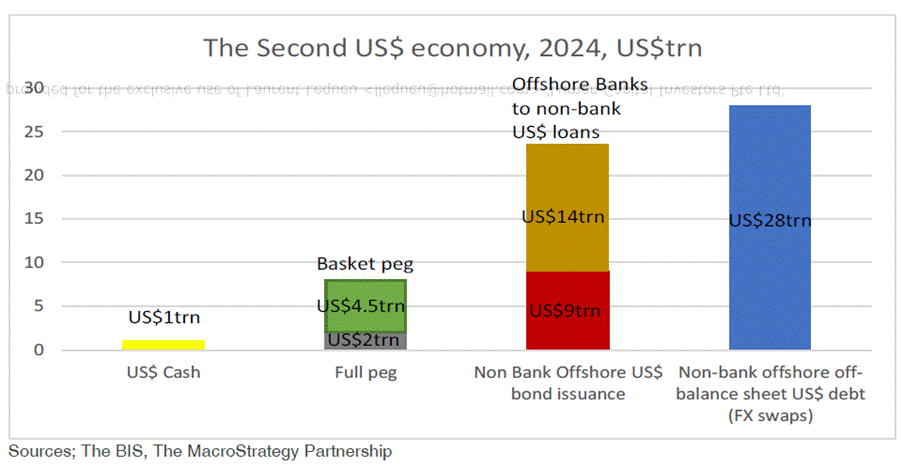

A generation later the same playbook is repeating—this time in India and Vietnam. By the late 2020s, Eurodollars may once again be paving the way for dams, ports, factories, and whatever else lenders can justify after a long lunch. Today, roughly US$55 trillion circulates in the domestic U.S. dollar economy, while about US$31 trillion sloshes around offshore in the Eurodollar market. The BIS adds another US$28 trillion in unhedged dollar FX swaps—essentially IOUs that behave like invisible dollars—quietly supercharging the whole system. In other words, the world is awash in dollars, and history suggests that where the dollars flow, the infrastructure soon follows.

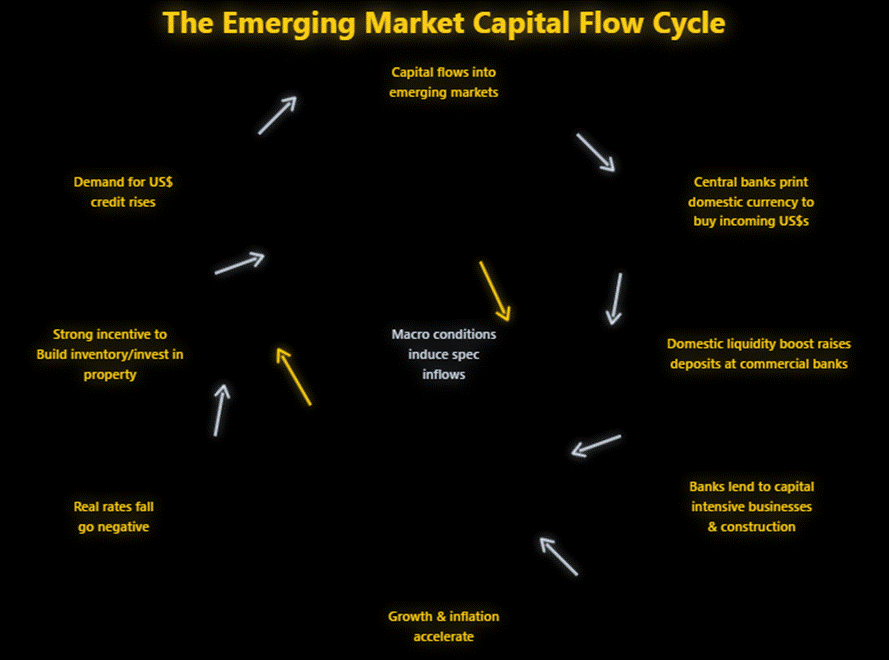

Throughout this entire period, U.S. monetary policy acted like the global tide, pulling capital offshore or pushing it back home. When the Fed turned on the money taps, dollars spilled overseas, making it cheaper and easier to finance commodity trades, global commerce, and emerging-market infrastructure dreams. When policy tightened, the tide went out—and everyone suddenly remembered how expensive dollars can be. The schematic below captures this global dollar dance in all its elegance.

Despite political dysfunction and towering U.S. debt, the dollar remains the world’s ultimate reserve because no credible alternative exists. It still accounts for roughly 59% of global reserves, while the euro—an idea Washington encouraged during the 1985 Plaza Accord—never fulfilled its promise. Europe refused to mutualize debt, ensuring the euro would lack the deep, unified bond market required to rival the dollar. China’s yuan is even further from contention, constrained by capital controls and political management rather than market confidence. History is consistent—from Rome’s denarius to Britain’s post-WWI pound: value follows confidence, not government decree. The dollar’s dominance is not proof of American virtue, but of global instability. Capital flows obey cycles, not morality.

At the Rome Summit in 1990, Thatcher’s resounding “No! No! No!” to deeper European integration marked the rupture that triggered Geoffrey Howe’s resignation and the cabinet revolt that ended her premiership—and cleared the political path for abandoning the pound in favor of a future euro. But the euro was always a political construct, not an economic one. Without a unified fiscal authority or a common debt market, it mirrors Europe’s divisions rather than its unity, and the FX market prices it accordingly. Each time Brussels calls for “solidarity,” capital instinctively migrates to New York, London, or Singapore. In today’s sovereign-debt contagion cycle, the euro’s vulnerability stems not from trade flows but from diverging confidence between northern austerity and southern insolvency. The ECB is trapped: raising rates risks breaking Italy, while monetization alienates Germany. This structural contradiction makes the euro the fault line in the next global realignment.

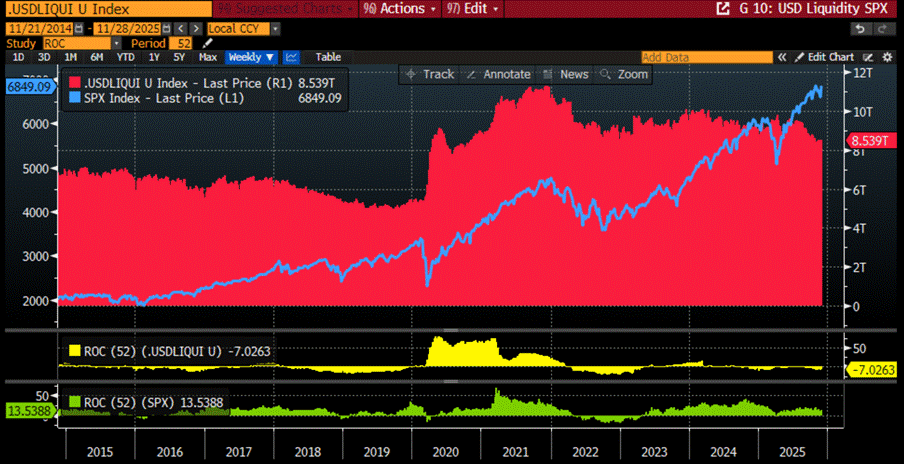

The simplest way to gauge the global dollar tide is by tracking excess U.S. dollar liquidity. A practical proxy is constructed by adding the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet to the Reverse Repo Facility (RRP) and then subtracting the Treasury General Account (TGA). Since the TGA functions as the U.S. government’s checking account, rising balances drain liquidity from the financial system while declines release dollars back into global markets. Historically, increases in excess USD liquidity have acted as a tailwind for U.S. equities, supporting both market performance and annualized rolling returns.

S&P 500 index (blue line); USD Liquidity Proxy Index (red histogram); 52-week rate of change in USD Liquidity Proxy index (yellow histogram); 52-week rate of change in S&P 500 index (green histogram).

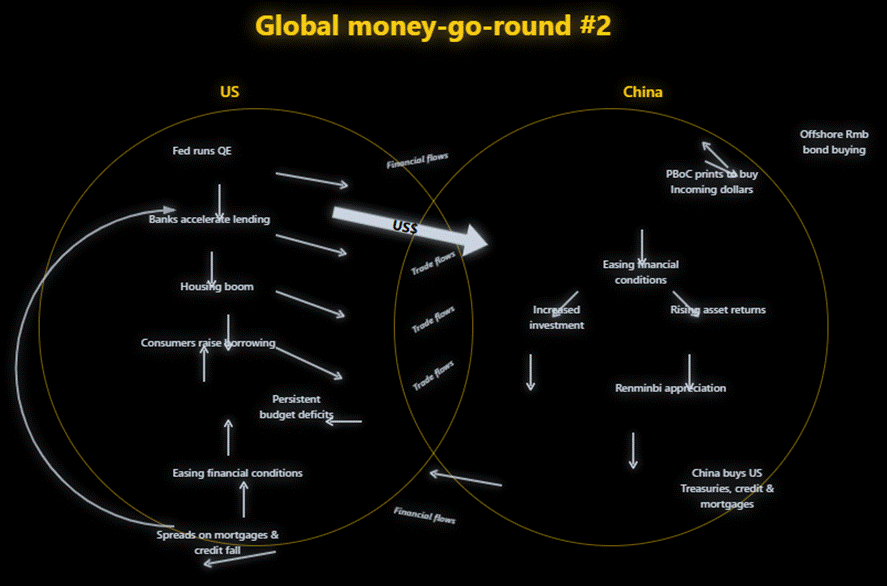

Global excess USD liquidity is like the planet’s investment thermostat. When it spikes, we’re in a reflationary boom—think party with stocks dancing. Stay too long, and delayed policy tightening (hello 2021-22) can trigger an inflationary bust, where both bonds and stocks stumble. The 2002-07 boom? China’s mercantilist faucet: incoming USDs met PBoC printing, fueling property speculation and local infrastructure mania. FX reserves circled back to US Treasuries, Greenspan nudged rates gently, and voilà—the global money-go-round #2, complete with low yields, surging property wealth, falling savings, and more dollars flowing offshore.

China’s efforts to internationalize the yuan have gained momentum, but limited convertibility and weak rule of law keep it from becoming a genuine reserve currency for the time being. Beijing can rally the BRICS on paper, but without true capital freedom, the yuan’s reach will remain regional. Japan, meanwhile, has reclaimed its role as the global funding hub: the yen’s slide beyond 160 per dollar reflects not only BOJ-Fed divergence but the deeper reality of Japan’s demographic deflation. Capital isn’t fleeing Tokyo speculatively—it’s reallocating strategically toward U.S. yields and faster-growing Asian markets.

https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/renminbis-unconventional-route-reserve-currency-status

Read more and discover how to trade it here: https://themacrobutler.substack.com/p/currency-regime-change-is-dollar

Join The Macro Butler on Telegram here : https://t.me/TheMacroButlerSubstack

You can contact The Macro Butler at info@themacrobutler.com

Disclaimer

The content provided in this newsletter is for general information purposes only. No information, materials, services, and other content provided in this post constitute solicitation, recommendation, endorsement or any financial, investment, or other advice.

Seek independent professional consultation in the form of legal, financial, and fiscal advice before making any investment decisions.

Always perform your own due diligence.

Contributor posts published on Zero Hedge do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of Zero Hedge, and are not selected, edited or screened by Zero Hedge editors.