Italy Takes Its Gold Ball and Goes Home

TL;DR: Italy’s attempt to reclaim its gold reveals deeper cracks inside Europe’s monetary system. As gold regains importance as geopolitical collateral, national governments are testing supranational rules that once limited sovereign control of reserves.

The Fight Over EU Gold Reveals a Fracturing Europe

Italy’s renewed effort to assert formal state ownership over its gold reserves has drawn objections from the European Central Bank, which argues that such measures threaten central bank independence. In strictly legal terms, the ECB is objecting to legislation that could transfer effective ownership or operational authority over official reserve assets from the Bank of Italy to the Italian Treasury. Beneath that legal dispute, however, sits a deeper institutional tension: meaningful national autonomy over gold reserve management was already surrendered years ago under euro-area treaties and coordinated policy frameworks, raising questions about what “independence” now actually means within the Eurosystem.

I. The Immediate Dispute

Proposed legislation in Rome would codify that Italy’s gold, currently recorded on the balance sheet of Banca d’Italia, ultimately belongs to the Italian state “on behalf of the people.” The ECB has reiterated concerns first expressed in a formal 2019 opinion, cautioning that any move that removes independent control of official reserve assets from the national central bank could violate treaty protections governing monetary financing prohibitions and financial independence. In the ECB’s interpretation, gold bullion constitutes part of a country’s official foreign reserves and must therefore remain held, managed, and operationally controlled by the national central bank rather than by fiscal authorities.

Who Controls CB Gold in The Euro Area?

GFN – ROME: Italy’s renewed push to assert state ownership over its gold reserves has triggered formal objections from the European Central Bank, which argues that such actions undermine national central bank independence. The dispute exposes a deeper tension embedded in the euro system: control over national gold was already centralized years ago under…

Under this framework, the issue is less symbolic ownership than balance-sheet placement and decision authority. Reserves that are transferred to direct state ownership, or reserves over which legislative bodies exercise binding influence, would compromise the principle that central bank assets must be shielded from political instruction. From Frankfurt’s perspective, Italy’s initiative is therefore framed not as a debate over patrimony but as a potential breach of institutional design.

II. The Earlier Centralization of Gold Policy

While the ECB now defends the autonomy of national central banks, material restrictions over national reserve management were introduced at the creation of monetary union itself.

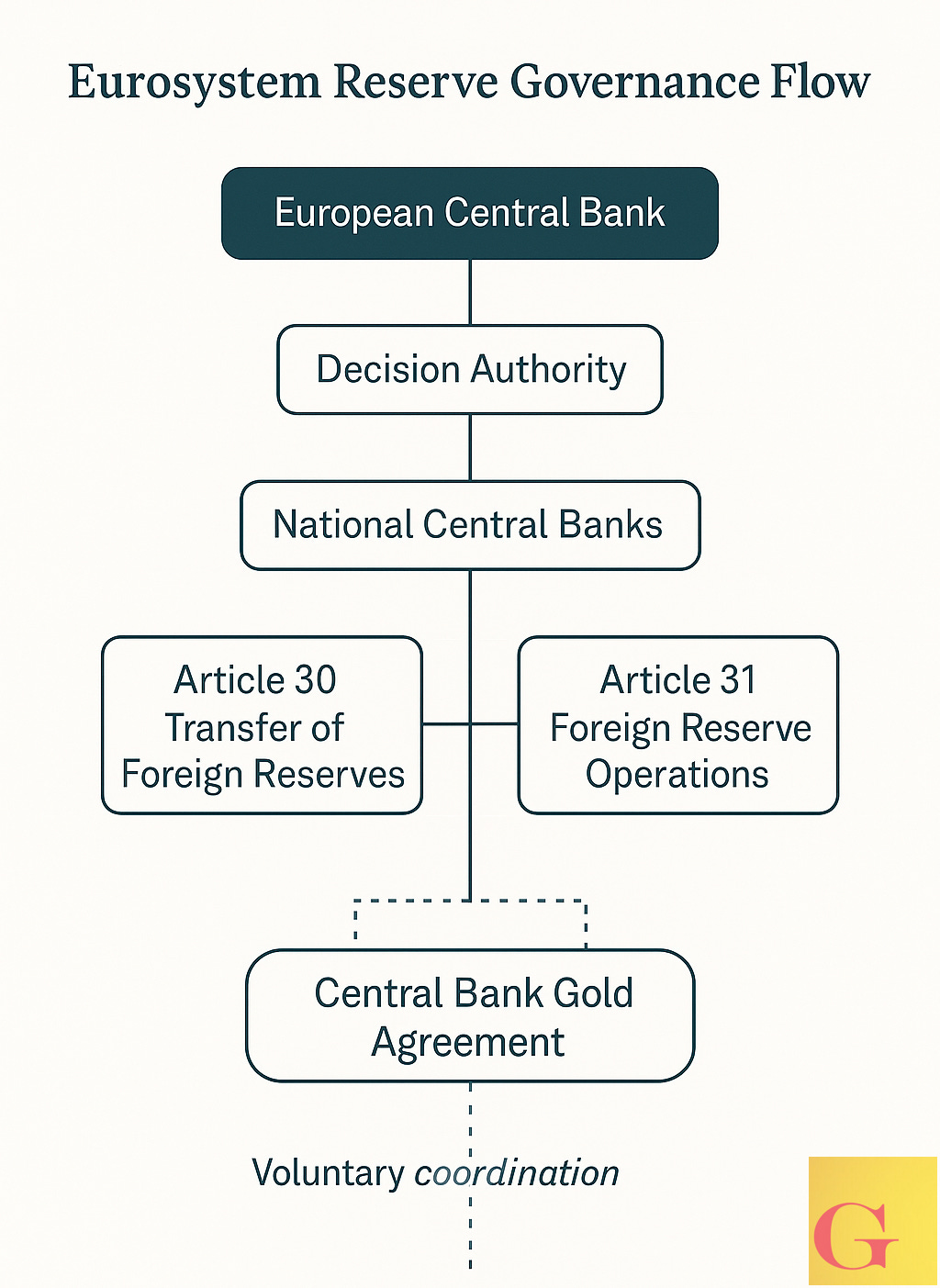

When Italy entered the euro area, it surrendered a portion of its foreign reserves to the ECB under Article 30 of the European System of Central Banks statute. Remaining reserves stayed on national central bank balance sheets, but Article 31 then subjected all significant foreign-exchange and gold operations to ECB oversight in order to preserve consistency with euro-area monetary and exchange-rate policy. National central banks retained custody of gold, but not unilateral discretion in its disposition. Sales, leasing, derivatives activity, and reserve conversion operations became subject to coordination and approval thresholds set at the Eurosystem level.

Italy's Gold Tax: Pay Now and Pay Later…

Good Afternoon: Italy is weighing a one-off tax amnesty to pull privately held gold into the formal economy, aiming to unlock billions in revenue and inject liquidity into a market long sustained by informal family transfers.

This system-wide constraint was further formalized through the Central Bank Gold Agreement framework beginning in 1999. Under successive iterations of the agreement, the ECB and participating national central banks imposed collective caps on annual gold sales and restrictions on derivatives activity to assure markets that European monetary authorities would not destabilize bullion prices through uncoordinated actions. Although presented as voluntary memoranda of understanding, these agreements functioned in practice as enforceable policy commitments binding participating central banks.

The outcome was a de facto centralized reserve governance structure. National central banks continued to warehouse gold within their vaults and maintain formal booking ownership, yet operational policy became subordinated to supranational constraint. The traditional model of sovereign reserve autonomy gave way to collective management under ECB governance.

III. What “Independence” Means Under EU Law

The ECB’s position rests on a narrow and highly institutionalized definition of independence. Article 130 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union prohibits central banks from seeking or accepting instruction from governments or national political authorities. It does not prohibit binding coordination imposed through the internal governance mechanisms of the Eurosystem itself. Independence within this doctrine is vertical rather than absolute; it means freedom from fiscal intrusion, not freedom from supranational monetary authority.

In practice, membership in the Eurosystem entails the transfer of substantial operational authority to the ECB Governing Council. National central banks participate in policymaking but remain subordinate to collective decisions once adopted. From a legal vantage point, this subordination is not viewed as erosion of autonomy but as the expression of independence at the systemic level. Political influence is barred; supranational monetary governance is permitted.

This distinction lies at the heart of the current conflict. The ECB views limits imposed by the Eurosystem as structurally legitimate expressions of monetary independence. Limits imposed by national legislatures upon their central banks are viewed as violations of the same principle.

IV. The Structural Contradiction

The tension arises from the difference between legal definition and practical sovereignty.

For more than two decades, Italy has not exercised sovereign discretion over its gold reserves in the classical sense. Operational decisions have been filtered through ECB approval frameworks and collective coordination mechanisms. Gold policy has functioned within a supranational management architecture whose purpose was to regulate aggregate supply behavior and preserve euro-area policy consistency.

From this perspective, the ECB’s objection to “nationalization” reflects a conceptual paradox. The autonomy it now defends is not the classical independence of a national central bank operating on behalf of its sovereign state. It is the independence of the Eurosystem as a centralized monetary authority operating above national governments. The Italian central bank remains autonomous only insofar as it executes policy within the confines of supranational rules.

Thus, Italy is not attempting to nationalize a free-acting central bank reserve portfolio. It is attempting to reassert legal ownership claims over an asset that has long operated under non-national governance. The political act seeks to recover sovereignty that monetary integration gradually eroded.

V. Why This Debate Is Re-Emerging Now

This dispute emerges amid a renewed global emphasis on gold as a geopolitical and monetary reserve asset. Outside the euro area, sovereign accumulation has accelerated, often with explicit policy objectives tied to reserve diversification, payment system insulation, and strategic autonomy. National control over bullion is increasingly viewed as an expression of monetary sovereignty.