The Grain That Shapes Power

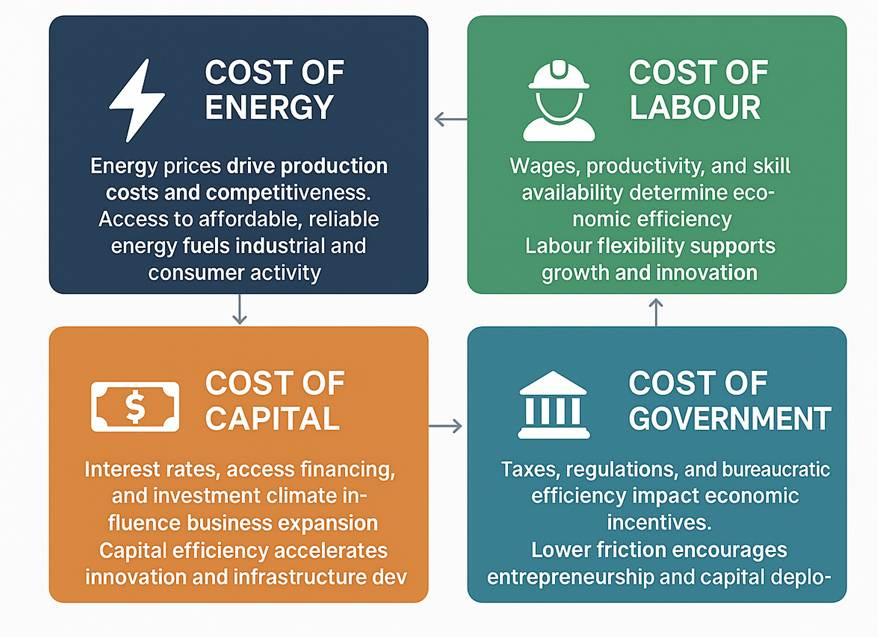

When Master Kong looked upon the markets, he might have said: “A nation that lets rice become gold will soon find its people eating sorrow.” The cost of food, like the cost of energy, is a pillar of prosperity because it keeps both families and the wider economy in harmony. When food prices are calm and modest, households have silver left to spend, merchants smile, and officials sleep soundly. Affordable food tempers wage demands, steadies business costs, and allows the economy to flow as smoothly as tea in a well-balanced cup. But when prices surge like an untrained horse, it strikes hardest at the humble, stirs discontent, and forces people to cut back on everything except necessity. Thus, while energy may fuel the machines of industry, food nourishes the people who operate them—and without both in balance, even the strongest kingdom can wobble like a three-legged table.

“When rulers try to command the price of bread, Heaven merely commands their exit.” Indeed, every empire that sought to fix the price of grain found itself fixed in the history books within a few short years. Yet Washington and Brussels now march proudly down the same well-worn road—proof that those in power study history only when it flatters them, never when it warns them. Their eyes remain glued not to the horizon of the nation, but to the next theatrical election, those grand rituals where everyone pretends choice is abundant and wisdom is in charge.

Across the ages, it was never invading armies that frightened rulers most—it was hungry citizens. Food shortages have toppled more regimes than sword or cannon. In 1529, during the chill of the Mini Ice Age, the people of Lyon erupted in riots over scarce grain. A century earlier, the Petite Rebeyne of 1436 saw wheat prices soar so high that thousands stormed the homes of the wealthy and poured the granary’s grain onto the streets in a symbolic gesture: “If we cannot eat, then neither shall you.” History whispers the same lesson again and again, but governments, like stubborn pupils, refuse to hear it.

When the student ignores the entire scroll, he blames the wrong chapter. Yes, climate has always moved in cycles—humans have lived through warm periods, cold periods, and even the sharp chill of the Little Ice Age. And indeed, the coldest point was around 1650, long before coal chimneys and oil derricks. But today’s climate zealots and climate deniers alike often commit the same error: they confuse past natural cycles with the present trend, which—according to every ‘Green Zealots’—is warming sharply and is largely driven by human emissions, not by the Sun’s whims or ancient oscillations.

Historical temperature series, whether from New York or Vienna or Tokyo, show natural ups and downs, yes—but they also show a clear upward trend over the past century and a half. At the end of the day, when the bamboo keeps growing taller, do not say it is standing still just because you remember when it was short. But here lies the true danger: in their zeal, some policymakers treat the climate challenge like a morality play rather than a logistical one. They imagine salvation in instantly banishing fossil fuels, forgetting that energy feeds industry, and industry feeds people. Rapidly cutting energy without ensuring stable replacements risks disrupting food production precisely when climate variability may make agriculture more fragile. Thus, if the ancients teach us anything, it is this: “Balance brings harmony. Extremes bring chaos.” We cannot pretend the climate is not changing. But neither should rulers rush into grand edicts that risk turning the people hungry—because as history has shown, nothing stirs revolt faster than empty stomachs and officials who refuse to learn from the past.

Everyone who look at history knows that when a ruler cannot feed his people, even the Mandate of Heaven files a complaint. Emperor Claudius learned this the hard way: Rome’s old river port at Ostia was so clogged with silt and inefficiency that Egyptian grain—the lifeblood of a million hungry Romans—arrived slower than an overworked donkey. Storms, shallow channels, and clumsy transfers from large ships to tiny boats turned the empire’s supply chain into a comedy of errors. After mobs hurled stale bread at him during a famine, Claudius finally built a grand new deep-water harbor with breakwaters and a lighthouse worthy of Alexandria. Naturally, Nero took the credit—proving that emperors change, but politics does not. Though the port still silted up until Trajan improved it, Claudius had made the essential leap: secure the grain or lose the throne. From the Republic’s subsidized “bread for the people,” to Caesar’s assassination amid shortages, to the Third-Century chaos, to Rome’s final collapse when the Vandals seized North Africa, the lesson echoed through the ages: control the wheat, control the people; lose the wheat, lose the empire. Even the Medieval Warm Period knew this truth—when the climate was kind and harvests were generous, populations flourished and rulers slept well.

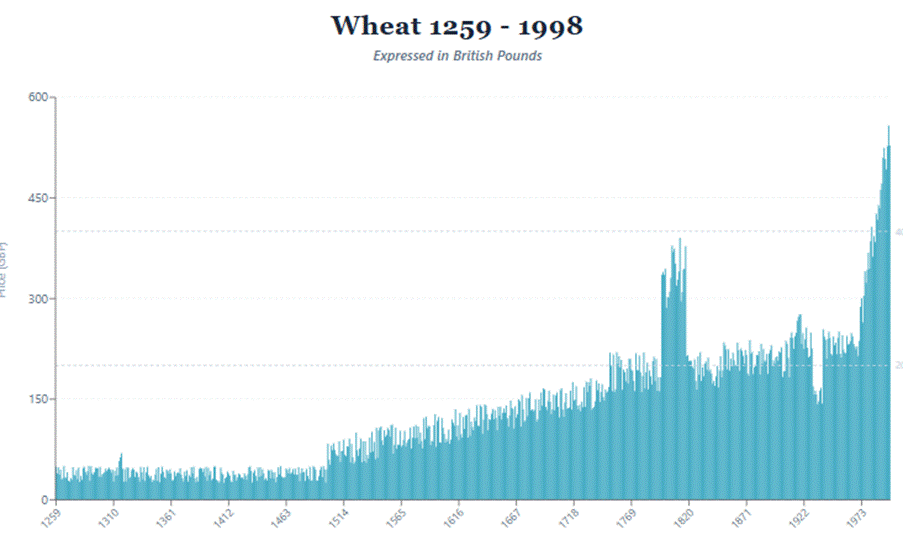

Fast forward a few centuries later, the climate decided to throw Europe a very unpleasant surprise party. Around 1315, the weather flipped into a cold, soggy cycle that drowned wheat fields faster than a drunk monk at a baptism. The result was the Great Famine of 1315–1317, where 10–15% of Europeans starved—history’s way of saying, “You thought you were in charge? How adorable.” And just when the continent was recovering from its forced diet, along came the Black Death (1347–1353), assisted by a population already weakened by empty stomachs. Wheat prices first shot up like an ambitious politician, then collapsed as half the labor force vanished. With so few peasants left, landowners discovered they actually had to pay people—a shocking innovation that helped end serfdom and nudge Europe toward early capitalism. In short, climate, disease, and demographics teamed up to deliver a brutal yet effective economics lesson: boom-bust cycles don’t care about your plans—they just show up, rearrange everything, and leave you to clean up the mess.

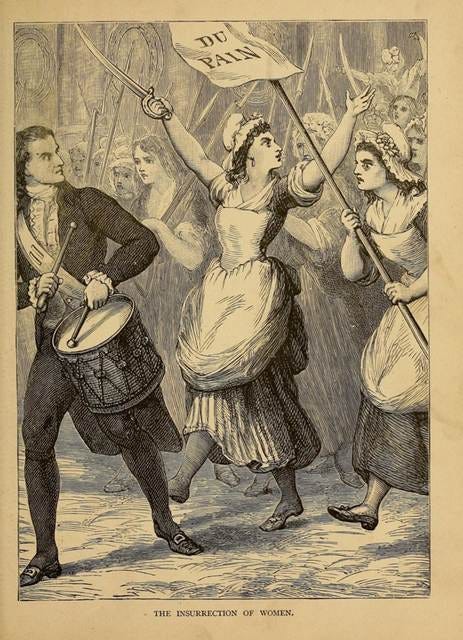

The “Price Revolution” of the 1540s–1650s was Europe’s first lesson in monetary mischief: New World silver flooded the system, inflation took off, and wheat prices quadrupled—an early warning that when governments print too much money, even bread starts acting like a luxury good. Fast-forward to 1788–1789, when France combined bad harvests with fixed bread prices, producing the predictable Orwellian result: chronic shortages, public rage, and a revolution that began not with philosophy, but with empty stomachs. The French Revolution toppled the monarchy, seized church lands, and sent anyone deemed too fond of royalty to the guillotine. Yet even after heads rolled, France’s real obsession—bread—remained unresolved. Just two days after proclaiming the lofty Rights of Man, the Assembly deregulated grain markets on August 29th, 1789, triggering panic about hoarding and speculation. Then, in October, a Paris crowd accused a baker, Denis François, of hiding loaves. A hearing proved him innocent, but the mob hanged and decapitated him anyway, forcing his pregnant wife to kiss his bloodied lips. Horrified, the Assembly declared martial law, discovering—too late—that revolutions driven by hunger rarely listen to constitutions.

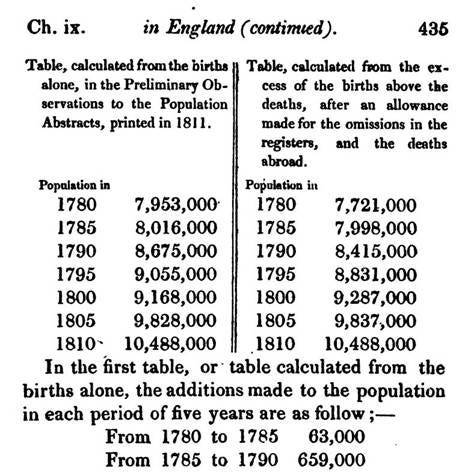

Bread shortages became so severe that riots erupted across France—the “Flour War”—long before the Revolution proper. Immigration swelled the population by millions, and bread consumed up to 80% of a worker’s income, turning every price spike into a political grenade. Myths like “Let them eat cake” (really: “eat the leftover crust from the pan”) became weapons in a propaganda war. The crisis fueled radical ideas, including the Paris Commune of 1793—Marx’s inspiration for communism—all because the breadbasket ran dry. Malthus, observing climate-driven crop failures since the 1650 Mini Ice Age low, warned in 1798 that population would outgrow food supply; many thought he was simply describing the obvious.

Into this chaos stepped Turgot, who recognized that overregulation was strangling grain production and delivered the timeless economic commandment: “Do not meddle with bread.” In other words, wherever governments try to manage the price of staple food, the outcome tends to look less like utopia and more like an early draft of 1984, with ration cards, riots, and a revolution waiting just offstage.

The Napoleonic Wars (1800–1815) led to blockades that disrupted wheat trade. This was part of an economic war as Britain faced periodic shortages. Then came the Irish Famine—the tragic moment when political incompetence shook hands with crop failure. Potatoes collapsed, wheat prices spiked worldwide, and the British Corn Laws helpfully transformed a disaster into a catastrophe. The result was predictable: ships packed with starving Irish sailed for the U.S., while London insisted everything was under control. It was the sort of policy success only a bureaucracy could celebrate.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6735970/

The cycle flipped again, ushering in the great Global Wheat Boom of 1860–1913, when the U.S., Russia, Canada, and Australia graduated into full agricultural superpowers. Cheap global shipping stitched together the first truly international wheat market, and the long commodity upswing pushed prices into a super-cycle by the 1890s, peaking just as WWI turned wheat into a matter of national security. Blockades, conscription, and collapsing production brought price controls everywhere—because nothing says “freedom” like government-approved grain.

Then came the Great Depression, when wheat prices plunged 60%, Dust Bowl farmers abandoned their fields for California, and the commodity cycle hit rock bottom well before WWII. The war brought a frantic agricultural mobilization, with wheat doubling as diplomatic leverage—Lend-Lease with calories. Europe, of course, had already learned centuries earlier that climate cycles are less forgiving than monarchs. Deregulation only fueled bidding wars and hunger, immortalized in tokens showing men gnawing on bones.

After World War II, the development of high-yield wheat varieties transformed global food production. Productivity soared, stabilising prices for decades. Then, in 1973–1974, the world experienced the Great Wheat Spike. The Soviet Union secretly purchased massive quantities of grain—later dubbed the “Great Grain Robbery”—sending global wheat prices sharply higher. This shock aligned with the early-1970s inflection point in the broader commodity cycle. By the 1980s, however, rising surpluses and a strong U.S. dollar suppressed prices once again.

Wheat surged back into focus during the 2007–2008 Global Food Crisis, when prices tripled and riots erupted across dozens of developing countries. The destabilisation that followed became a direct precursor to the Arab Spring. In recent years, wheat has re-emerged as a strategic asset. As Russia rose to become the world’s largest exporter, the weaponisation of wheat became evident during the Ukraine War. Supply chains—already strained during the COVID period (2020–2022), with its politicised lockdowns and global disruptions—again faced severe pressure. With both Russia and Ukraine being major exporters, the conflict has raised renewed fears of structural shortages. Wheat prices have spiked across North Africa and the Middle East, reminding us of an old lesson: when war disrupts grain flows, political instability is never far behind.

https://medium.com/something-about-everything/food-riots-and-the-arab-spring-4886e4c3604

History rhymes: food is the quiet tyrant behind many uprisings, and we are entering another cold phase of the climate cycle while pretending climate only changes when CO₂ rises. A deep Ice Age is still centuries away, but shorter, harsher growing seasons are enough to strain supply. Ukraine—Europe’s breadbasket—is a war zone for more than 3 years, and escalating the conflict in hopes of “defeating Russia” risks wrecking the farmland that feeds millions. With leaders chasing geopolitical glory rather than peace, shortages after 2024 are not a possibility—they’re a trajectory. As ever, politicians start wars, but it is the hungry who start revolutions.

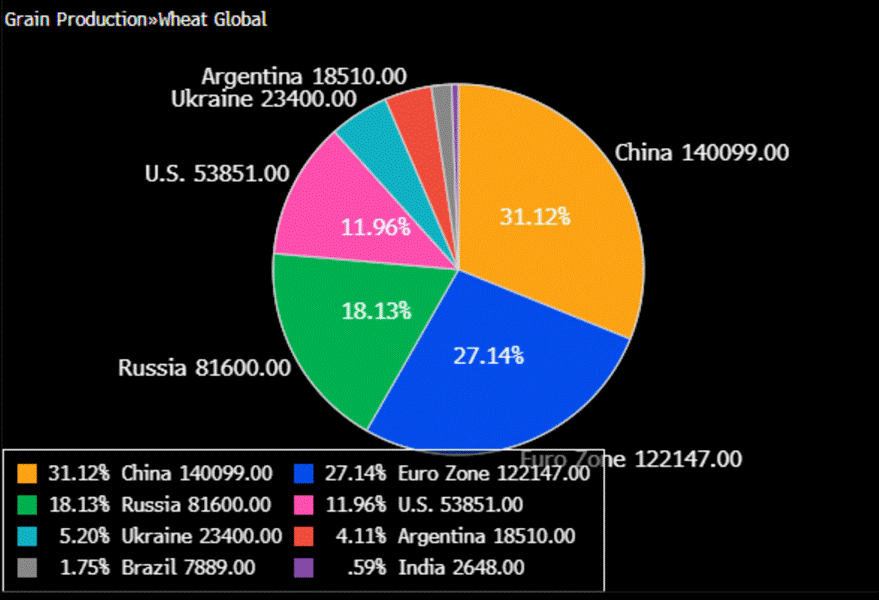

Common sense pledges that ‘A kingdom that feeds itself need not fear rebellion—but one that depends on others may awaken the guillotine.” The world’s largest wheat producers are, in a sense, the guardians of global stomachs. China and India lead the charge, wielding vast fields and government plans as if they were ancient scrolls of wisdom, ensuring their people never starve. Russia, meanwhile, has cultivated the Black Sea’s bounty into an empire of grain exports, quietly reminding the world that fertile land can speak louder than armies. The United States continues its tradition of mechanical mastery, producing wheat with the efficiency of a disciplined mandarin scribbling in his ledger. France and other European nations contribute their precision and technology, ensuring their harvests remain as orderly as a Confucian ceremony. Together, these wheat powers govern the ebb and flow of supply, trade, and prices—proof that while philosophers debate virtue, it is bread that truly keeps the world in harmony.

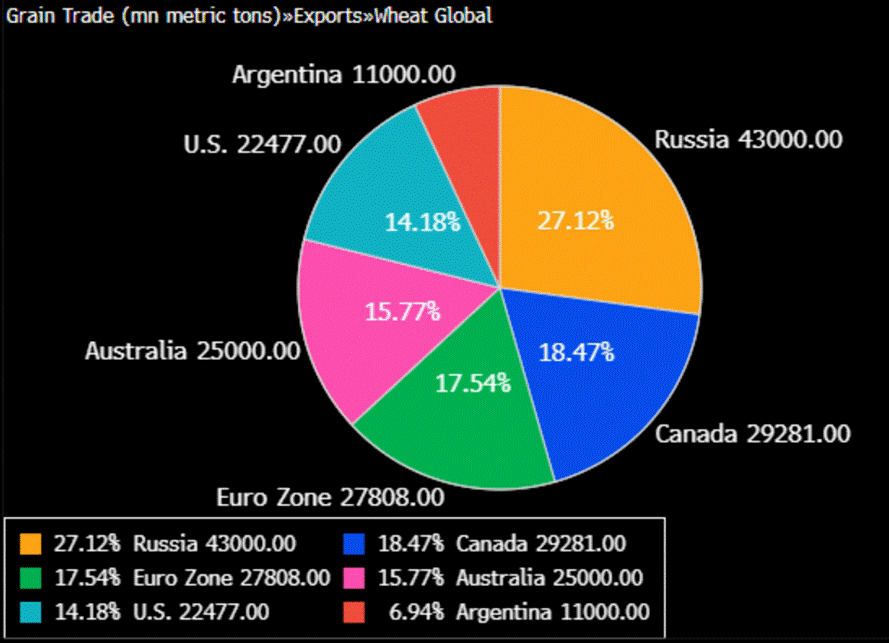

In the global wheat export arena, Russia is currently playing king of the grain hill, projecting a record 53 million tons for the current marketing year—enough to claim a 26% share of the world market. That’s the highest market share in Russia’s history, proving that when it comes to wheat, Mother Nature and the Black Sea are very good allies. Hot on its heels are Australia and Canada, duking it out for second and third place, proving that even in the wheat world, there’s always room for a polite rivalry… and maybe a little bragging at the annual grain conference.

Wheat is not just a commodity—it’s history’s favorite weapon, having toppled more empires than gunpowder. The current 2021–2025 bear market is merely the calm before a historic surge. This isn’t inflation—it’s systemic scarcity colliding with war, climate volatility, and monetary chaos.

Read more and discover how to trade it here: https://themacrobutler.substack.com/p/the-grain-that-shapes-power

Join The Macro Butler on Telegram here : https://t.me/TheMacroButlerSubstack

You can contact The Macro Butler at info@themacrobutler.com

Disclaimer

The content provided in this newsletter is for general information purposes only. No information, materials, services, and other content provided in this post constitute solicitation, recommendation, endorsement or any financial, investment, or other advice.

Seek independent professional consultation in the form of legal, financial, and fiscal advice before making any investment decisions.

Always perform your own due diligence.