Top Goldman Software Analyst Unveils 12 Lessons From Three Decades Of Tech Cycles

We've reached a stage in the AI cycle where listening to industry insiders and veterans who've lived through multiple boom-and-busts actually matters. Their perspective is uniquely helpful in figuring out whether this boom still has real momentum rolling into 2026 - or if the runway is already running out of pavement.

Leaning on Kash Rangan, a Managing Director and Senior Equity Research Analyst at Goldman Sachs, who on Tuesday published a new client report titled "12 Lessons Over 30 Years as a Software Analyst."

Here are those 12 lessons:

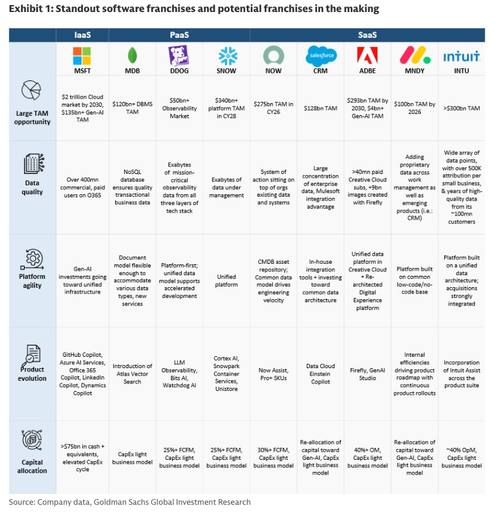

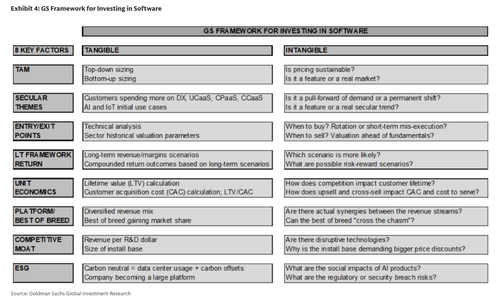

1. It generally pays to be very discerning: Creating a scaled and profitable software franchise is very hard. There is a reason why there are only a handful of enterprise/business software companies generating more than $10 bn in revenues outside of the Mega caps like MSFT and ORCL. That list includes CRM, ADBE, INTU, NOW, and WDAY. Most companies that start out with plenty of potential in the $100-500 M revenue range don't make it into large cap land. It pays to be selectively optimistic most of the time on a few companies' ability to scale profitably. But it is acceptable to be very discerning of the average company's ability to scale when the category is unproven. One must critically examine the category and assess the depth of the problem which warrants an innovative solution before entertaining ambitions of a large TAM etc. The most successful companies don't start with a large TAM; they start with a solution that the market is badly in need of. That creates and grows a TAM. Software is a product that can create attention and desire in the mind of the buyer through the promise of business transformation. Once the category is created, the TAM follows. Some of the smaller companies within our coverage that have a shot at scaling into much larger companies in revenues are SNOW, DDOG, MDB, RBRK, IOT, MNDY, TTAN and FIG. It's hard to make the call that all of them will get to $10 bn in revenues, but we believe they have the most potential today.

2. Successful value creators compound growth in good and bad times; their runway prolongs the path to maturity: Investors may recall looking at DCF models ages ago that 'assumed' GDP-type growth 5 years out for historically higher growth franchises like CRM, INTU and ADBE. Several years later, they were still exhibiting above GDP growth. We prefer to own software companies that can outgrow GDP significantly for as long as it can. It's a good thing when companies keep pushing out that GDP-type growth way into the future in the DCF. The problem with mature growth at scale is that it becomes hard to accelerate unless it's a company like MSFT or ORCL, and they discover an opportunity with the cloud and AI infrastructure buildout. That acceleration has already happened. INTU's forward LT guide for potential acceleration at scale over the next 5 years offers a glimmer of similar potential. On the topic of steady compounders at attractive growth, ServiceNow has been steadily clocking ~20% during good and bad times largely organically at a +$10 bn scale. Based on our model and the market opportunity, it would be hard to envision maturity anytime soon. That reminds us of CRM which compounded at an organic growth rate north of 20% at $10 bn scale between 2018-2020 to effectively double its revenues to $20bn.

3. Successful companies have high R&D and new products, but within reason: This sounds simpler than it is. Software companies are good at creating new products. But the good long term value creators put out new products at a cadence that customers can absorb and implement successfully. On the other hand, ones that live off a hit product which can take them from $0 to $100 million very quickly but don't do much to create adjacencies are bound to hit a wall. In the early stages we would look for high R&D as % of revenues. But the core product must be making attractive profits. It's ok for the new products to lose money. But as the company gains scale, the R&D leverage has to kick in. Otherwise, there could be a problem. In other words, long-term value creators will get to operating profitability scale in core products one and two before investing in the third. The cycle continues with products three and on.

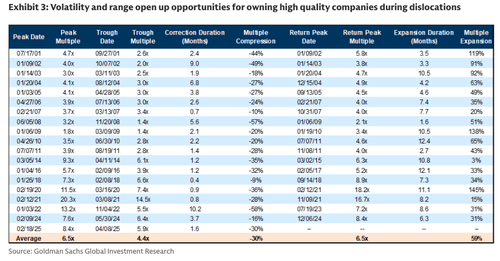

4. A formula based on organic growth will generally find it hard to accommodate M&A: Salesforce was primarily an organic growth company for the better part of a decade since it went public in 2004. A move to an M&A approach in the 2018–2020-time frame was something unsettling to investors even though core organic growth was healthy and the acquisitions were well-conceived as part of evolution into a multi-cloud platform. The reason was the acquisitions took away from operating leverage for a few years. Subsequently, Salesforce revitalized growth with strong operating leverage and went on to create value but not till the M&A overhang cleared. Oracle too went on an M&A approach in 2004–2009-time frame by being a smart acquirer at attractive valuations and while investors did not appreciate that approach at first, the company grew shareholder value by creating operating and EPS leverage even through inorganic growth. In that vein, ServiceNow will be closely watched to see if acquisitions are 'additive' to the underlying organic growth without throwing a wrench in the operating margins, which was historically a stumbling block for Salesforce.

5. Incumbents get tougher to dislodge with every cycle, especially the larger ones: Investors don't fully appreciate the power of incumbency at transition points in important tech cycles. The Street is more apt to apply a forward penalty for disruption to incumbents at a transition point between cycles such as the period we are going through now with AI. We went through something similar in 2001-2004 which resembled a chasm between on premises and cloud. It felt as unsettling back then as it feels for software investing these days. Companies that survived the shake-out and consolidation in the aftermath of the 2001 bubble went on to be strong creators of shareholder value. Cases in point -- Intuit, Adobe, Autodesk and of course the big three Microsoft, Oracle and SAP. None of these companies got disrupted although they all began their tech and business model transformations at different points in time. At several points, every one of them looked very vulnerable, on the edge of single digit P/E multiples and single digit growth. However, they used the cloud cycle to become larger, more profitable and faster growth businesses that drove collectively more market value than all cloud native business software companies that went public in the 2010-2020 timeframe. So, we would be careful when betting against incumbency. The good companies figure it out before the market does. We are making a not-so-subtle point about SaaS incumbents these days. We would not write them off.

6. Companies that maintain a good balance between growth and FCF margins generally do well across growth and defensive cycles: Companies that go for all-out growth with little or no profit margins will be rewarded in a low-rate growth cycle. But that can be tricky as we approach a rate-tightening cycle. That forces companies to go for profitability by winding down growth. They can then fall into this cycle of having to show better profitability since that becomes the new formula. That's not enough to keep the stock price moving higher since they are going through the dreaded rotation from growth to harvesting for margins. Inevitably, a new cycle like AI kicks in and they need to get into a re-investing mode, which becomes hard since they have spent so much effort in cutting back on growth in return for profits. On the contrary, when a company is ingrained with a profit AND growth mentality from a relatively early stage and keeps a good balance like, say, a Microsoft, ServiceNow or Intuit -- such a company will outperform in the long run.

7. Transitions between tech cycles can be unsettling but can also provide opportunities if investors have duration: Transitions such as the one we are going through (Cloud to AI) can be unsettling. Perhaps not disruptive to cloud infrastructure but maybe to platforms and applications. While MSFT made a rapid pivot to AI, the others are getting there. The guarded outlook that Wall Street harbored towards platform companies like Snowflake, Datadog and MongoDB has alleviated as investors have grown to appreciate the value of data in the enterprise AI cycle. As perceptions shifted, sentiment changed and thanks to stable to slightly improving growth, these stocks doubled within the space of a year. But that was not before a very unsettling period with limited sponsorship. Although a bit dated, we distinctly recall how unsettling the 2001-2004 time frame was not only because we came off the dot com valuation bubble but software applications built for the on-premises era were seeing sharp declines in growth and profitability as uncertainty about the next tech wave set it. The seeds of what we call the cloud cycle started with the Alphabet IPO in the consumer world and Salesforce IPO in the business world, both in 2004. Even then, a real cloud cycle in software did not get going till 2010-2021 when we had a solid cohort of IPOs including ServiceNow, Workday and Snowflake. Earlier in that time frame, Adobe, Autodesk, Intuit and even Microsoft and Oracle went through periods of intense investor uncertainty and low valuations as they went through their own re-invention for the cloud world. As they went through a tumultuous phase to reinvent themselves, a wide trading range and frequent selloffs opened several opportunities to own successful franchises at attractive values at times of dislocation.

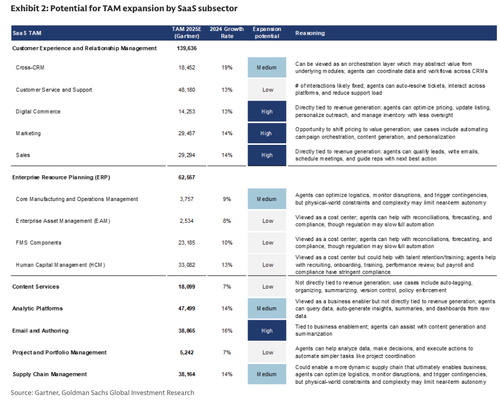

8. Multiple ways to create value - TAM supports growth duration, unit economics supports margins and acquisitions support growth adjacencies: It's rare to find an objectively large TAM and attractive unit economics in a company. When we get that combination, that's usually the recipe for long term value creation. Even at large cap scale. TAM can be somewhat contested and subjective at a time of technological change. When a company claims a TAM which is, say, 15-25x its revenue and it's revenues are growing 10%, that means the TAM is likely overstated. A large TAM with not-so-great unit economics can still lead to meaningful value creation. Salesforce had (and still has) a significant TAM but one comprised of different adjacent markets. This meant that building a broad product platform and a multi-specialty GTM covering different markets required them to invest heavily in S&M. This can lead to not-so-great unit economics since specialty sales and overlays are needed on top of the distribution. Let's just define unit economics as S&M (non-GAAP) divided by new revenue (excl renewals). Effectively, in financial terms, what are you spending to acquire a $ of new revenue? When Salesforce was a single product company, the economics were solid at ~$1.1 of S&M for a $1 of new revenue. Several years into its evolution into a multiproduct platform generating 20% growth, the unit economics eroded to $2-2.20. That was OK since they traded OM for scaled revenue. In simple terms, the investor should be better off with a business at 2x the scale with two products generating ~20% OM than a single product company at half the revenue scale generating say 30%, especially if the two-product company grows faster even while dragged down by lower margins.

Acquisitions generally are thought to break the organic growth formula. But even expensive acquisitions can drive value when the acquirer has the distribution and the customer base to be able to drive multiyear growth. One thing that gets overlooked in the focus on organic vs acquired growth is that in year two, the organic growth of the acquirer generally accelerates, especially after the deferred revenue write-down normalizes. Microsoft has made notable such acquisitions, which worked out well for a long duration (Linkedin and Github are notable examples). Even Salesforce, while drawing much attention to the acquisition of Slack in 2020, has realized a lot of synergies whereby now the acquisition has become a key part of its AI platform. Workday is another example whereby the acquisition of Adaptive allowed the company to establish a foothold in the large and enduring market for financials applications. In that context, we view ServiceNow's proposed acquisition of Moveworks as a strategic positive.

9. Mature companies can create significant value through predictable if not outsized growth with OM expansion: The problem for software companies sets in when they go below 20% growth. Multiples get challenged as rotation from growth to GARP takes over in the investor base. Then, companies must work their way to higher OM in return for lower growth. However, that transition to higher OM can be a value driving phase as well, which is what CRM went through in 2023 when OM increased by ~800 bps. If we look at a scaled business like ORCL (before the AI/IaaS wave), despite being a multiproduct company, the business was able to generate 45% OM by holding unit economics at relatively attractive levels. CRM's long term OM guidance of ~40% suggests that the unit economics are likely to go back to such attractive levels. When a company gets everything right -- scale, OM (more or less a function of unit economics since S&M is the largest expense item for a non-hyper-scaler software business), TAM and secular tailwinds that can support durable growth even at low levels (sub-20%), it can be a strong combination. Case in point - MSFT and INTU, which have been the steady compounders. We would closely watch ADBE given the transition to AI. The stock has struggled, but the business has been doing quite OK if we look at the annual progression of ARR, revenues and EPS.

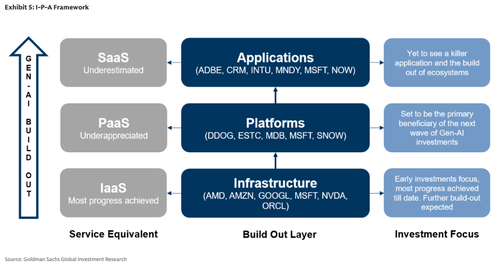

10. Infrastructure, Platforms then finally Applications is a logical progression in a tech cycle but there can be growth scares in that progression: The AI cycle right now is dominated by an infrastructure buildout which has gone longer and deeper that it has naturally provoked questions about the return (application) on investment (infrastructure). While it may be tempting to conclude that the foundation models could own the full stack of AI, one must maintain a level of openness to the broadening out of the cast of beneficiaries and the possibility that foundation models become platforms that promote an ecosystem with new AI applications revenues. We are reminded of the bear case on SaaS in 2016 when AWS became widely appreciated for the strength of its cloud-native infrastructure and platform offerings, which investors extrapolated into possible disruption of the cloud applications (SaaS) landscape (CRM, WDAY, NOW, etc.). Ironically, AWS ended up facilitating the growth of cloud applications by providing supporting infrastructure and platforms and even becoming a business distribution vehicle through its marketplace. We see a potentially similar dynamic between foundation models and SaaS incumbents. The bottom-line is that applications companies are good at solving business problems on a repetitive scale and platform companies provide the technical foundations to help in that enablement. The industry rewards specialization and variety as cycles progress.

11. The price must be right, the functionality must be better and the profits have to be there for disruption to be enduring: Having witnessed disruptions in prior cycles we note that price and functionality need to be orders of magnitude better than incumbents for disruption to take hold. Putting a wrapper on a foundation model and passing through high inference costs via API calls through a consumption model can generate revenues quickly but will mean low gross margins and possibly even low retention. That may be OK in the beginning to get going but it's a delicate dance since the value added can be competed away by the foundation model. And the lower the GMs the longer companies must fight it out and get to a large revenue scale before turning an operating profit. In prior cycles, platforms and applications had clear boundaries and dependencies. As an ISV (Independent Software Vendor), companies could count on ORCL, MSFT or IBM to release a great database and the companies would hasten to make their application take advantage of the new things in the latest database release. Although it's tempting to conclude that foundation models will the vertically integrated powerhouses, specialization along the lines of history (infra/platforms/apps) could very well be the way that things could regress in this AI cycle.

12. Tempting to think that the supply of capital at low rates coupled with propensity to accept large losses is more conducive to disruption: Maybe the investment cycle in AI can go for longer under private sponsorship than it could if it were under the scrutiny of the public markets. And it has been that way for a few years now. We are not strangers to 'lower' gross margins in a new cycle. We saw that with infrastructure and applications in the cloud cycle. SaaS GMs were not anywhere close to on premises. But it was OK since the cloud cycle created much larger businesses even while taking a hit on higher COGS. Scale won over margin %. In this cycle, as AI companies have been rewarded with capital and healthy valuations even with lower GMs than the cloud cycle, the revenue scale to achieve 'acceptable' GMs is much greater. This is while the foundation models must recoup their heavy investments by way of large API fees at inference time. The question is, will there be enough customer spending to go around to keep everyone happy with acceptable margins.

This brings us to the idea of 'residual value'. In the cloud world, hyperscalers initially led with low GMs for compute and storage but then made attractive recurring revenues at higher margins with platforms as a service. This created attractive 'residual' value by way of recurring high margin revenues by way of a platform which was necessary to run applications. In fact, hyperscalers like MSFT excelled in applications at scale too. Interestingly, in the AI world, there are at least three groups of entities – foundation models, hyperscalers and the wrapper/applications companies built on foundation models.

The natural question is who has the residual value by way of recurring revenues (reminds one of SaaS) after the training is over? Hyperscalers like MSFT and Alphabet have residual value - MSFT has exclusive IP access to OpenAI and Alphabet is unique since they have first party infrastructure, platforms and applications. How will the economics otherwise in the industry be split? Who is entitled to the platform and applications revenues in broader AI land? Who can deliver the full stack? And after all this split is done what is the margin for the different entities? Coming back to the heart of the initial disruption hypothesis, regardless of how all this plays out, even private market investors will start to demand real economic profits after some time and so will public market investors eventually.

Whereas what is not being appreciated is that applications companies like MSFT, CRM, ADBE, INTU, NOW, ORCL, WDAY and others may be in a position one day to arbitrage away the competition between the foundation models (given the number of competitors) and drive the cost of intelligence lower by emerging as the orchestration layer which could simplify things for customers. Not to mention the fact that they have the data and context advantage. One more reason why we would not rule the incumbents out of the AI debate.

Professional subscribers can read much more from Goldman's analysts team here at our new Marketdesk.ai portal